Rice is the staff of life for the Japanese and many Asian countries. Learn about its long historical significance and impact on Japanese culture.

Rice is an intrinsic part of Japanese cuisine and culture, eaten daily in Japanese homes (traditionally, for every meal!) There are also religious customs and festivals deeply rooted in rice cultivation.

A glimpse into the history shows that rice is more than a mere foodstuff. Rice provides nourishment and has played a vital role in Japan’s development into the country known today. In this three-part series on rice and Japan, let’s first delve into the history of Japanese rice.

Table of contents

Meaning of Rice

Linguistically, rice is synonymous with the meal. ‘Cooked rice’ or gohan (ご飯) is a meal. When your mom says, “It’s Gohan!” it means “It’s time to eat!”

Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are respectively Asa-gohan (朝ご飯), Hiru-gohan (昼ご飯), and Ban-gohan (晩ご飯), ingraining a bowl of rice at every meal.

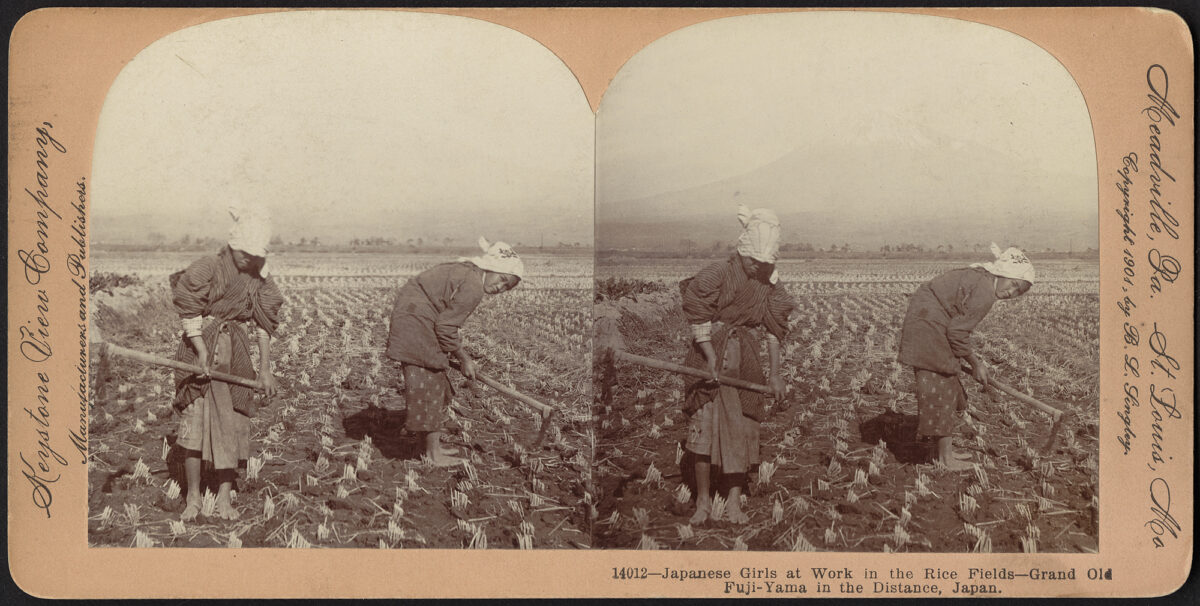

The Early History of Rice Cultivation

Rice is believed to have been first cultivated in southern China or somewhere in eastern Asia 10,000 years ago and introduced to Japan from China or Korea. The earliest record of rice cultivation in Japan dates back to the late Jomon era (around 400 BC) in the southern island of Kyushu.

Its cultivation gradually spread across the country, where hunter-gatherers became agrarian societies formed around rice farming. The Itazuke archeological site (板付遺跡) in Fukuoka prefecture is the earliest settlement where excavations revealed rice paddy fields, irrigation channels for diverting river water, and storage for rice.

Rice cultivation requires communal effort and cannot be done alone. It is a labor-intensive task involving many steps, where fellow farmers pool their manpower to share water resources, ward off pests, and help each other with planting and harvesting the crops. This necessitated an emphasis on collective group interest and formed community groups called Yui (結), which became the foundation of Japanese society.

Even though only a tiny percentage of the Japanese population are rice farmers today, the Japanese continue to sustain group harmony in the relatively small island nation. Thus, Japanese society’s group consciousness and consensus-seeking mindset can be traced back to rice cultivation.

Rice as the Life-Blood of Government and Society

Over time, rice became a tool of control and dominance. Rice signaled wealth and was used to rank one’s social status among the upper elites.

From the 7th century to the Edo period (1603-1868), the peasant class was forced to pay taxes to the feudal lords in the form of rice, and the samurai received their salary in rice, which they sold the excess for cash.

The Tokugawa Shogunate taxed the feudal lords based on their administration’s total economic yield and territories. Kokudaka (石高) is the annual yield value of land, which was measured in rice where one koku (一石) was the equivalent of enough rice to feed one adult man for a year (roughly 150kg of rice).

The historic city of Kanazawa, under the rule of the Maeda clan, was the wealthiest clan in feudal Japan, second only to the Tokugawa Shogunate. The Maeda clan had an accumulated net worth of one million koku (百万石; 1 million koku = 5 million bushels/48 million gallons of rice) and rightfully earned the nickname Kaga Hyakumangoku (加賀百万石; Kaga was the name of the territory). The lavish and beautiful temples, castles, and historic buildings of Kanazawa are a testament to the Maeda clan’s vast economic power.

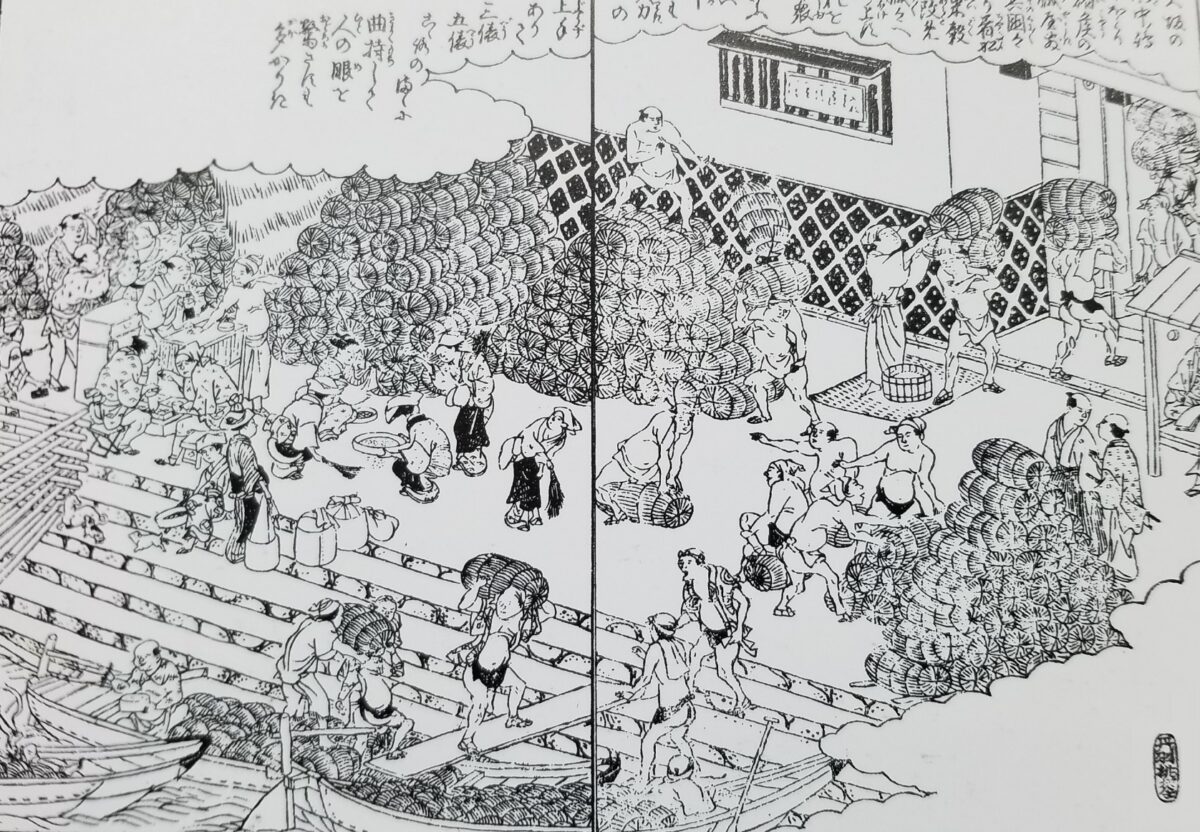

The Earliest Japanese Banking System

As mentioned, the samurai and feudal lords were paid rice, not cash. The uneaten rest was exchanged for currency since one cannot sustain on rice alone. This sparked the emergence of independent brokers, money changers, and rice markets, which played a crucial role in establishing the early modern banking system and the advancement of a currency-based economy.

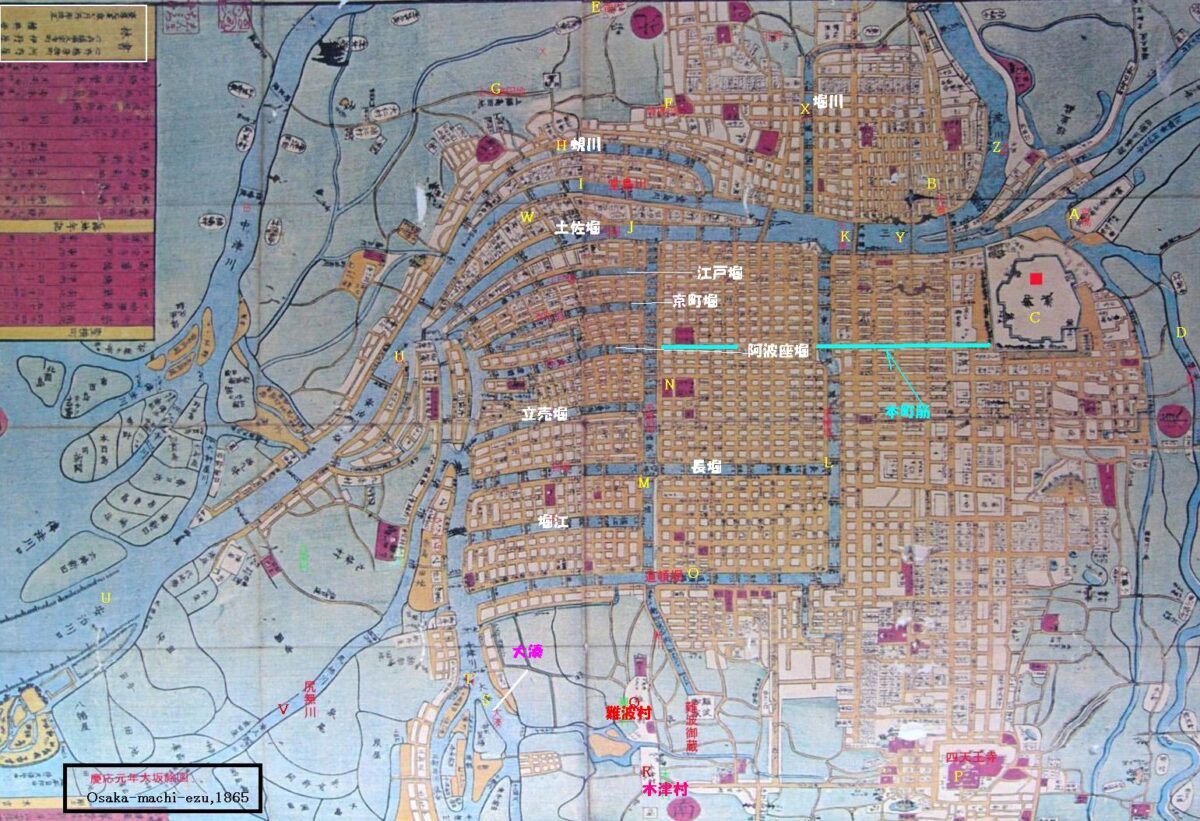

While Edo (modern-day Tokyo) was the political capital during the Edo era, Osaka was the trade and commercial epicenter due to its pivotal location as a port city smack in the middle of the country.

Rice and other foodstuffs and goods collected by feudal domains were shipped to Osaka and then sold to brokers through auctions in exchange for paper money. The rice and goods were shipped to feed the hungry Edo capital, which by 1700 had grown into the world’s largest city, boasting a population of over a million.

The Dojima Rice Exchange

The Dojima Rice Exchange (堂島米市場) in Osaka was established in 1697 and later officially authorized by the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1730. By 1710, the world’s first futures trading on rice transactions, Nobemai (延米), was born.

What set Dojima apart from other world markets was that the nation’s monetary transactions were handled through these powerful and independent merchants of Dojima. They managed the bank accounts and financial transactions for many feudal lords and samurai while the Shogunate struggled to regulate them.

Dojima flourished for over 300 years until it was reorganized, then dissolved by the Japanese government in 1939 and replaced by the Government Rice Agency.

White Rice for All?

As removing the rice bran was labor-intensive, white rice was mainly reserved for the upper class. The lower classes subsisted on brown rice, other grains such as wheat and millet, and starches such as potatoes.

It wasn’t until the Meiji era (1868-1912) that the industrialization of rice processing made white rice available and affordable to the masses. White rice was scarce again during the food shortages during and post-WWII.

The circumstance was countered by the U.S. occupying forces’ push for a wheat-based diet. American aid (and also propaganda) in the form of wheat flooded Japan, where the rice-dependent population grudgingly incorporated more wheat into their diet to offset the rice scarcity. School lunches served bread instead of rice to mold the younger generation’s dietary preferences. The soldiers and returnees from Manchuria (northern China) brought wheat noodles and gyoza, popularized among the hungry population (more on Chuka Ryori, Japanese-Chinese cuisine).

Fearing that the population would completely shift to a wheat-based diet, the Japanese government and various interest groups campaigned for the return to a rice diet in the 1970s. But rice consumption never returned to the prewar era.

Rice Today

In recent years, per-capita rice consumption has declined due to the shrinking population. This can be attributed to the diverse side dishes currently served at a Japanese meal (一汁三菜) compared to the Edo era, the shift to a Westernized diet, the availability of other cuisines, improvement in economic conditions, and the surging popularity of a low carbohydrate diet, which has exacerbated the decline of the rice heavy meal.

Despite all these factors, rice cultivation remains heavily subsidized by the Japanese government. The government implemented a rice tariff scheme in 1999 to protect the domestic rice industry and support Japanese food security. The flood of cheap imported rice and lowered tariffs was a concern of national security interests and threatened a solid national identity ingrained in rice.

However, multiple attempts have been made by major rice growers such as the U.S., Thailand, and Australia to negotiate lower tariffs to make way for their rice exports. Thus, in 2017, Japan imported USD$358.3 million in rice, where 58% was from the U.S., 39% was from Thailand, and 1.9% was from Australia.

Japan was the third-largest export market for the U.S. rice industry that year. Japan also imports rice products such as rice flour, crackers, and noodles from Thailand, China, the U.S., and Vietnam.

These days, you can purchase California-grown Calrose rice and other short-grain rice from Australia and China at Japanese supermarkets. The stigma against imported rice is gradually waning, although many Japanese people prefer domestic rice, even if the price is higher.

Part 2 will uncover how rice plays an essential role in Japanese culture through religion, mythology, and customs.

Is rice a staple food in your country? How did rice play an essential part in your culture’s history? How do you eat Japanese rice? Please share in the comment box below!

That was great! I know so much more about rice now…..

Hi Bonnie! Aww. We are glad to hear you enjoyed reading this post!

Thank you so much for your kind feedback.🥰

Thanks for the super informative article!! When will part 2 be available (or is it already available)? Looking forward to reading it!

Hello Juliana, thanks for reading!! Part 2 should be out the end of this week, please stay tuned!

I’m from Sri Lanka. Historically one of the oldest rice cultivating nations in the world and currently the 9th highest per capita consumer in rice. We also have over 1000 native varieties of heirloom rice varieties to show off so to say rice is important to us is an understatement! We have managed to use rice in many shapes and forms to make our meals not only diverse but very exciting! From sweet deep fried rice fritters to savoury rice puddings to the staple rice and curry most of us eat rice in some shape or form pretty much three meals a day. But interestingly we do not have brown rice here. Instead the bran colour of all rice varietals are red, hence the name of our main staple, red rice. I know that Japan has some red heirloom rice varieties but for some reason they are prohibitively expensive to eat at a regular basis which was surprising to me since white rice was only for special occasions when I was growing up!

Hi Ruwindu! Thank you for sharing the history of rice in Sri Lanka. I didn’t know there are over 1,000 native varieties of heirloom rice!! I can’t imagine how diverse the traditional meals must be. That’s so interesting that red rice is the staple in Sri Lanka. Yes, we do have Japanese red rice (赤米), but over time it got phased out due to its low crop yield compared to short grain rice. But in the last 3 decades, there has been growing interest in heirloom rice varieties, including red rice but it is usually mixed in with white rice instead of eaten on its own.

Hi Nami,

I think I’ve shared this story of riceballs for lunch before, but wanted to share again. In the early 60’s we lived on Navy housing but went to public schools in SF and Long Beach Cal. My mother would make riceballs for my brown bag lunch. Kids in my classroom would want to trade their sandwich for my riceball. I made out, everyday i would get either a ham and cheese or peanutbutter and jelly sandwich. Today, I still pack riceballs for snacks or lunch, especially when we go on road trips. My grandkids still request riceballs and fried egg on rice when i come to visit….My mother always told us never waste a grain of rice, cause their is 7 gods in every grain and rice is to precious to waste. I licked my fingers everytime I ate my riceball, even today.

Hello Diana san, this is Kayoko, author of this article. Thank you for sharing your onigiri story! Yes, the Japanese (and perhaps many other rice eating cultures as well) believe that there are gods/spirits/deities in grains of rice and scold children never to waste. I’ll touch upon this topic on part 2!