Learn more about the history and cultural significance of Wagashi, traditional Japanese confections. From local specialties and seasonal varieties to everyday desserts, you’d gain a much deeper appreciation as you enjoy the sweets year-round.

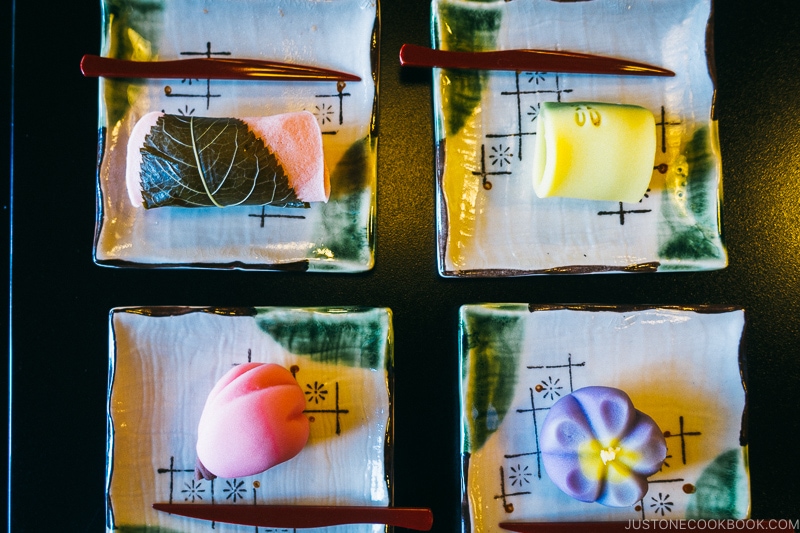

You may have seen beautiful pieces of sweets displayed in a confectionery section of Japanese department stores or supermarkets. Some resemble motifs from nature, such as flowers, leaves, or fruits. It may be made of bean paste, mochi, or jelly-like substance. They look more like miniature pieces of art. Are they edible? And does it taste as good as it looks?!

Called Wagashi (和菓子), these Japanese confectioneries carry a rich history entwined with Japanese culture. There’s more than meets the eye (and stomach)!

In this two-part series on Wagashi, let’s first explore its cultural and historical significance to the Japanese.

Table of contents

What is Wagashi?

The term Wagashi encompasses all Japanese desserts, from the tea ceremony delicacies to the everyday desserts. You may have seen them featured in Japanese movies or dramas, such as Dango (団子 skewered mochi balls), Dorayaki (どら焼き small pancakes sandwiching a sweet filling), or Sakura Mochi (桜餅 cherry blossom pink mochi with red bean paste inside).

Compared to European desserts, characterized by the abundance of butter and eggs, traditional Wagashi calls for minimal oil, spices, and dairy products. Most are plant-based, with minimal animal products. The main ingredients are grains such as wheat or glutinous rice flour, anko sweet red bean paste, kinako soybean powder, agar/kanten as a firming agent, and sugar. However, Wagashi masters also note trends and incorporate non-Japanese ingredients like ice cream, custard, and chocolate to create new edible delights.

Wagashi comes in all shapes and sizes, but most are small enough to be eaten within two or three bites.

Wagashi and Japanese Tea Ceremony

How does wagashi pertain to the Japanese tea ceremony? In a Japanese tea ceremony (茶道) context, Wagashi is served to accompany and complement the bitter taste of Matcha (抹茶 powdered young green tea leaves). Wagashi is always consumed before the Matcha is served and never together. The idea is that before drinking the savory and vegetal tea, you eat the sweet dessert to balance your month.

The deep appreciation of the seasons is reflected in the aesthetics of Wagashi. For example, you may see plum blossoms and cherry blossom motifs in the spring, young green bamboo leaves and fireworks in the summer, autumn foliage, chestnuts, and the harvest moon in the fall, and snow in the winter.

However, Wagashi isn’t limited to the tea ceremony scene; it can be eaten like any other dessert for midday, afternoon tea, or a post-meal dessert. You don’t need to pull out your matcha whisk and bowl; you can pair it with other green tea, non-green teas, coffee, or whatever you prefer!

To understand the world of Wagashi, let’s first understand its history.

The History of Wagashi

As stated above, the history of Wagashi and the Japanese tea ceremony (茶道) are intricately linked. It’s impossible to separate the two when approaching their respective origins.

Ancient artifacts show that the Japanese have been craving sweetness, going back to the Yayoi period (300 B.C.-300 A.C.) when the people ate the natural sweetness found in fruits and nuts.

Trade with the Sui and Tang Dynasties during the Asuka period (538-710) brought back various Chinese confectioneries. One called Kara-kudamono (唐果物), a type of deep-fried mochi made from rice, wheat, and soybeans, is said to be the origin of Wagashi. However, these delicacies were served at the Imperial Court and religious deities and not circulated among the commoners. Sugar was a luxury import good that was rare, and its primary use was for medicine.

Different types of Kara-Kudamon (Source)

Tea was introduced from China around the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and Zen monks’ habit of drinking tea was established around this time. A simple meal called Tenshin (点心 dim sum) and snacks were served as part of the ritual. As sugar was still not readily available, the sweet substance was made of the sap of grape ivy (甘葛). The meal served with the tea ceremony (茶席) became more elaborate during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), as Zen became connected with the upper Samurai class.

The availability of sugar became more widespread due to the Portuguese merchants, who introduced new cultures and cuisines to the Japanese. The Japanese aristocracy was hungry for Portuguese delicacies, and they adapted it into what was called Nanbangshi (南蛮菓子). These exotic sugar and egg-loaded sponge cake Castella (カステラ) and colorful sugar crystals Kompeito (金平糖) (from the Portuguese confectionery ‘Comfit’) were only for the nobility.

The Burgeoning of Wagashi in Japan

The demand for and production of Wagashi exploded during the Edo period (1603-1867) due to widespread commercialization throughout the country and a significant improvement in agricultural productivity. Sugarcane from Okinawa and Shikoku and processed white sugar became available in the capital (Edo) and Kyoto. This spurred the development of new Wagashi specialty stores. In parallel, the tea ceremony culture also flourished, where serving delicious sweets became one of the most critical aspects of the ceremony.

Edo-period booklets depicting various types of Wagashi.

With the fierce competition among Wagashi confectioners to meet their hungry customers’ demands, different styles with intricate designs became popular. Kyoto-styled Wagashi, Kyo-gashi (京菓子), was a beautiful edible art for the tea ceremony. In contrast, the middle-class Edo (Tokyo) craved the simpler and more approachable Jyo-gashi (上菓子).

The term Wagashi was born during the Meiji era (1868-1912), during the era of rapid modernization and westernization. Like how Washoku (和食) was a term to distinguish from foreign food cultures, Wagashi – wa (和 Japanese) and kashi/gashi (菓子 sweets) – were born.

Ready for More?

The traditions of Wagashi still live on to the present day. If you’re visiting Japan, stop by a tea shop to sample a few pieces with a cup of tea. You can find shops and stores serving wagashi in major tourist areas like Kyoto and Kanazawa and big department stores. If you’re in a small town, check out the local varieties. Some places offer classes on how to whisk a cup of matcha!

The next post will cover more of Wagashi’s different varieties and categories, covering topics such as Nerimono/Nerikiri, Higashi, and the different ingredients used to make it. Thank you for reading until the end, and stay tuned for Part 2, Varieties of Wagashi (Traditional Japanese Sweets).

To learn how to make Wagashi, check out Nami’s recipes:

- Ichigo Daifuku 苺大福

- Manju 饅頭

- Mizu Yokan 水羊羹

- Hanami Dango 花見団子

- Warabi Mochi わらび餅

- Anmitsu あんみつ

- Taiyaki たい焼き

Sources:

- The Essence of Japanese Cuisine: An Essay on Food and Culture (Source)

- The Japan Wagashi Association (Source Removed)

- National Diet Library, Japan (Source)

- Wagashi: Japanese traditional sweets or works of art? (Source Removed)

- 全国菓子工業組合連合会(全菓連) (Source Removed)

Hello,

I am a college student taking Japanese and I was curious if it would be ok for me to cite your Wagashi Guide articles to go with my research presentation I’m doing on the subject. I will also try making Nami’s Mitarashi Dango recipe to help me engage with my topic further (and try to share pictures of them). I really love both of the articles about the rich history and explanation of the different varieties, which made it so much easier to understand.

I am also a big fan of Just One Cookbook in general because it’s my go to website/blog to make Japanese recipes from (my favorite recipes are Miso Chicken and Salmon in foil 🤤 ).

Thank you so much for all of your articles and recipes 🤗. I always look forward to new recipes from JustOneCookbook and will suggest it to my class mates for recipes, along with JustOneCook’s other articles about travel and other cultural aspects of Japan 日本.

Hi Jordan, thank you for reading and for following JOC!

I am personally fine with my articles being cited for your papers, but you may want to check your university’s guidelines. For example, the University of Cambridge does not consider blogs as suitable sources.

https://www.research-integrity.admin.cam.ac.uk/research-integrity-guidance/citing-blogs-reference-sources

It may be best to find published works on the topic. Good luck!

Thank you so much for the post which was very enjoyable and informative without being boring. Looking forward to more.

Hello Nancy, thank you so much for reading! Hope you check out my other posts on Japanese food culture and history. Enjoy!

Wagashi article is so beautiful with nice product photos.

I really miss Japanese confections.

Hi Fumiko, thank you for comment! If you’re missing Wagashi and can’t buy them, please check out Nami’s recipes to recreate them at home. Good luck!

Hola

Me gustó mucho su publicación.

Donde puedo leer la siguiente?

Gracias y disculpe

Hola Gian, muchas gracias for your comment. Please also read Wagashi part 2 for more.

https://www.justonecookbook.com/wagashi-varieties/

Very interesting article about wagashi. Thanks for always enlightening us, readers. Arigato.

Jolene

Hi Jolene, thank you for reading and for your comment! Please stay tuned for Part 2 (coming soon)! – Kayoko

Wow, what a fun post! I learned a TON — thanks. 🙂

Hi John! Thank you for your comment! There will be a part 2 so please stay tuned 😀

Thank you so much for this informative wagashi article – the photos are beautiful! I took a wagashi cooking class the last time I was in Tokyo and if your readers visit Tokyo, I highly recommend it. I gave my creations to my son and his Japanese wife, and they thought I had bought them at a wagashi shop! I was so happy!! The cooking school is Buddha Bellies Cooking School and they offer several different one-day classes. It was a lot of fun and it was nice meeting other people from around the world who were interested in Japanese cooking, too.

Hello Shirley! Thank you for your comment! A wagashi class is definitely one way to learn and appreciate the craft of these edible delights, so glad to hear you enjoyed your class! -Kayoko

Thank you for your response and the information about the classes you took, Shirley. I’d like to take a class one day.

Fascinating, thank you for the lesson!

Hi Kevin!

Thanks for reading and for your comment 🙂

– Kayoko

Good informative article and am looking forward to part 2! I saw how the seasons are important to the making of wagashi and its relationship with the tea ceremony from an older drama from about 10 years ago called Ando Natsu (a girl’s name and the running joke was her parents must have loved donuts to name her that!) The lead played a jobless patissiere that found work assisting an old wagashi shop in Asakusa and ended up learning the craft. The drama highlighted how much thought and effort goes into making the sweets and was very interesting.

Hi Roy!

Thank you for your comment and yes, please stayed tuned for part 2! I watched Ando Natsu ages ago, such a cute drama! I don’t remember a crazy plot line, but it was a great insight into the world of wagashi. Too bad there hasn’t been any good dramas focusing on wagashi as of late… “Kantaro: The Sweet Tooth Salaryman” has some episodes of Wagashi shops…

– Kayoko

I am a sansei who grew up with not much of a Japanese-based background for cooking. I so very much appreciate your website and blog and look forward to everything you publish. I am a 70-year-young Deacon in a Christian Presbyterian church that has roots in the Pasadena, California area. Our parents settled here after World War II as did many other niseis.

Currently I am in charge of “Caring Cooks” a small group of church members that prepares a bento-style lunch for those that are homebound or in assisted-living facilities. The niseis are in their 90s and appreciate Japanese dishes. I look forward to trying out your recipes for sushi and the many other dishes you have prepared on your blog. This month I will prepare some miso vegetable pickles, chirashi and, hopefully, a confection from today’s blog.

Again, thank you for helping me to become the “Japanese” I was meant to be. I would appreciate more information on your cookbooks so I can refer to them often.

Hi Virginia! Thank you so much for your kind words. We’re happy to hear you enjoy our contents on JOC.

Thank you for sharing “Caring Cooks” with us. What a wonderful group of people! I receive a lot of feedback from Sansei and Yonsei wanting to learn Japanese food to feed their parents and grandparents who wish to eat only Japanese food (I can relate, too; I get older and I miss food I grew up eating). I believe what you do really brings joy in their life.

Unfortunately, I only sell e-Cookbook, and not a hard book. Maybe one day…

Thank you very much for your kind note. Please feel free to reach out to me if you need any information, etc. 🙂