Traditional Japanese confections, known as Wagashi, are delightful tea treats. It’s an art form that serves meaningful purposes and traditions of the Japanese culture. In this guide, we’ll explore the different varieties of these tempting sweets. Also, don’t miss our recommendations on where to shop for your enjoyment!

In Japanese food culture, the enticing world of Wagashi (和菓子) is vast and encompasses a wide range of confectionaries. More than just traditional Japanese sweets, Wagashi is a testament to the creative and evolving art of Japanese cuisine.

Wagashi masters keep a diligent eye on consumer demands and new technology. As such, you’ll spot trends of non-Japanese influences incorporated into the art that delights and competes for the senses. There are also regional styles, where Kansai (Osaka and Kyoto region) and Kanto (Tokyo region) fiercely defend their distinctive wagashi.

It’s not hyperbole to say that there are a thousand ways of making the same Wagashi as there are Wagashi masters.

Following Part 1 of the Wagashi Guide, we’ll dive into the wondrous varieties of traditional Japanese sweets. From the ingredients and production method to the seasonality and occasion of their appearances, you’d be mesmerized by how intricate the art can be.

Oh, we also include some recommendations on where to buy these Japanese sweets, both in Japan and internationally, at the end of the article! You wouldn’t want to miss out.

Varieties of Japanese Wagashi Sweets

Wagashi can be loosely categorized into three main groups based on its water content.

Then, each category is separated into subcategories based on its production method or ingredients. This type of classification is fluid and murky since no specific rules or governing bodies pin down the parameters.

1. Namagashi (生菓子) or Fresh Confectionery

- Sweets with a moisture level of 30% or above.

- As they are highly perishable, the sweets should be refrigerated and consumed by the next day.

a) Mushi-gashi (蒸し菓子)

b) Mochi-gashi (餅菓子)

- Made of glutinous rice or Japanese short-grain rice.

- Examples: Mochi (餅), Sekihan (赤飯), Dango (団子), Sakura Mochi (桜餅), Daifuku (大福)

c) Nagashi-gashi (流し菓子)

- Contains a coagulating ingredient traditionally made from plant-based Agar (アガー) or Kanten (寒天), sugar, and bean paste (餡).

- Examples: Mizu Yokan (水羊羹), Kingyoku (きんぎょく)

d) Yaki-gashi (焼き菓子)

- Wagashi that undergoes heat in a mold or flat pan.

- Examples: Imagawayaki/Obanyaki (今川焼き・おばん焼き), Dorayaki (どら焼き)

e) Neri-gashi (練り菓子)

- Consists of bean paste or glutinous rice flour and may use grated mountain yam as a binder. The paste is then kneaded and shaped. This is the classic Wagashi you will be served at a Japanese tea ceremony.

- Example: Nerikiri (練り切り)

2. Han-Namagashi (半生菓子) or Semi-fresh Confectionery

- Sweets with a moisture level of 10-30%.

- They should be refrigerated and consumed within 5-7 days.

a) Oka-gashi (岡菓子)

- Assembled

- Wagashi, where each part is prepared separately (often under different subcategories) and assembled.

- Examples: Monaka (最中), Kanoko (鹿の子)

b) Yaki-gashi (焼き菓子)

- Cooked

- Wagashi that undergoes heat in a mold or flat pan.

- Examples: Momoyama (桃山), Chatsu (茶通), Castella (カステラ)

3. Higashi (干菓子) or Dry Confectionery

- Sweets with a moisture level of 10% or less.

- The most shelf-stable of the three, it should be consumed within 1-3 months.

a) Beika (米菓)

b) Uchi-gashi (打ち菓子)

- Made of powdered glutinous rice flour, roasted barley flour, chestnut flour, or roasted soybean flour and sugar soaked in starch syrup, molded and dried in hot air.

- Examples: Rakugan (落雁), Wasanbon (和三盆)

c) Age-gashi (揚げ菓子)

Note: Some fall under Namagashi and Han-Namagashi, depending on how it’s made.

Wagashi Based on Occasion

In Japanese culture, serving and gifting Wagashi is an occasion, not a post-meal dessert. Here are the different occasions where you may encounter it.

1. Chaseki-gashi (茶席菓子), or Japanese tea ceremony

During a Japanese tea ceremony, Wagashi is served and consumed before green tea. For Koicha (濃茶), “thick tea,” Namagashi (usually Nerikiri) is served, whereas for Usucha (薄茶), “thin tea,” Higashi is usually served. The Wagashi is usually small enough to be eaten in two or three bites, and its design and name are deeply rooted in the season.

2. Hiki-gashi (引菓子), or Japanese wedding favors

If you attend a Japanese wedding, you will receive a goody bag with an odd number of gifts (even number is said to be taboo as in “splits the couple”). Traditionally, it would contain red and white Manju or mochi (red and white being auspicious colors in Japan). Nowadays, it’s common to see other types of Wagashi or Western confectioneries.

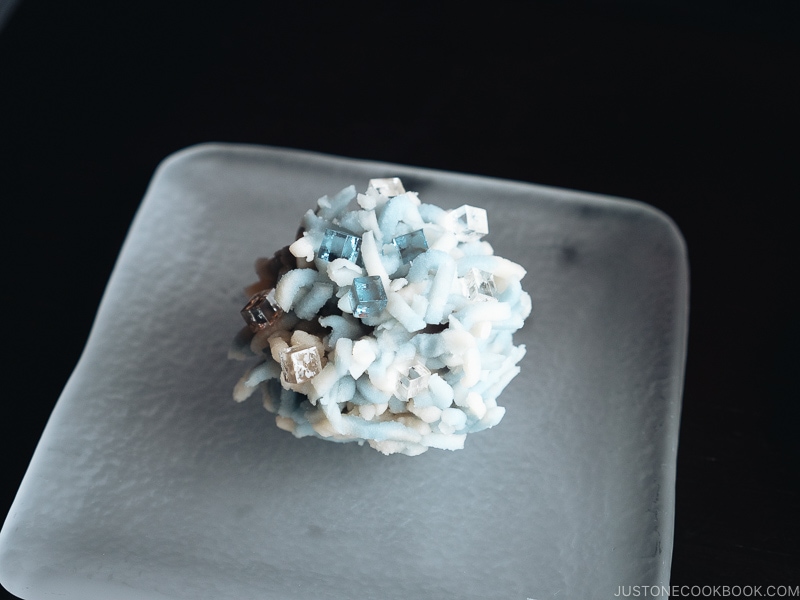

3. Kougei-gashi (工芸菓子) or Decorative Wagashi

Not for eating but a treat for the eyes only, the tradition of Kougei-gashi began in the late Edo period as a gift to the women’s quarters of the Shogunate. Nowadays, you may see these splendid displays showcasing the master’s craft at Wagashi shops, temples, hotels, and convention centers. The decorative sweets are mostly made of powdered sugar and granulated sugar, with motifs inspired by nature.

Seasonal Wagashi

The Japanese take immense pride and joy in the four distinct seasons, which is reflected in Wagashi. From the ingredients, colors, and poetic names, these seasonal Wagashi are eaten at special events and served as an offering to the ancestors.

For example, you will see cherry blossoms motifs and cherry blossom used as an ingredient during the spring season.

Japanese New Years:

- Kagami mochi (鏡餅)

- Hanabira-mochi (葩餅)

Spring:

- Sakura mochi (桜餅)

- Hanami-dango (花見団子)

- Kusamochi (草餅)

Summer:

- Kashiwa-mochi (柏餅)

- Kuzu-kiri (葛切り)

Autumn:

- Tsukimi-dango (月見団子)

- Ohagi (お萩)

Winter:

- Chitose-ame (千歳飴)

- Inoko-mochi (亥の子餅)

Famous Wagashi Producers with International & Online Shops

As I mentioned in Wagashi Guide Part 1, you can purchase Wagashi at the supermarket, on the ground floor of department stores, or at local shops. If you’re not in Japan, you could always try recreating these delightful sweets at home with Nami’s recipes. You could also learn about it from Instagram or your local Asian or Japanese supermarket. Some Wagashi shops have branches abroad and offer online shipping, so check them out!

Toraya (虎屋)

This humble family-run company has made red bean paste since the 16th century! They ship their Wagashi internationally and sell their products online on Amazon. Their products are sold on the ground floor of major department stores in Japan. I recommend stopping by any of their shops or cafes when visiting Japan, especially their beautifully renovated Asakusa flagship store or factory in Gotenba. They serve excellent red bean desserts (order their bean paste shaved ice and Anmitsu!) and a side of hot or cold tea. Their international post is a tea salon in Paris.

Minamoto Kitchoan (源吉兆庵)

If you’re curious to explore the wide variety of Wagashi, this is where to start! The shop boasts various seasonal Wagashi and contemporary interpretations like elaborate fruit jellies, bite-sized mochi, and matcha cookies. You’ll be mesmerized by the beautiful craftsmanship. Take home a selection of goodies for yourself or a special someone. They have a few shops in the U.S. and locations in Asia and London. For those in the U.S., you can easily order the treats online on their website.

Ippodo (一保堂)

With Wagashi, you need tea! Ippodo, based in Kyoto, has locations around Japan, and some of their major tea lines are sold at supermarkets. They offer a vast range of teas, from high-end to everyday favorites, and different grades of Matcha. If you find yourself in Kyoto or Tokyo, check out their salon for an afternoon tea break and Wagashi. They ship internationally and have one store in NYC.

Lastly…

Now that you have learned the basics of Wagashi and how to tell each variety apart, I hope you’ll spread the love of Wagashi to friends and family. Don’t let the dizzying options intimidate you! After all, Japanese sweets are for your enjoyment and enrichment as you sip tea.

To learn more, you can always browse through Instagram with the hashtag #Wagashi #和菓子 or check out the official Instagram accounts of Wagashi stores. My recommendations are Toraya, Ippodo, and Higashiya.

For those who wish to get their hands on Japanese sweets making at home, here are some easy Wagashi recipes:

Hi, Kayoto,

I am a student to take baking course in Canada.

I am researching about Wahashi and have found your useful articles.

Thank you so much.

In order to cite your articles in my project, I need more your information as an arthur, especially your last name. If you don’t mind, could you please send me your last name through e-mail?

And I am curious that Wagashi is popular in all areas of Japan and many Japanese are enjoying them in anytime or in specific days with teas.

I am looking forward to your reply.

Hello Jenny!

Thank you for your comment and I’m honored that my article has been helpful for your research!

My full name is Kayoko Hirata Paku, which is also listed on the JOC team intros.

Wagashi is found throughout Japan, with regional variations and enjoyed by the young and old. Traditionally, it is enjoyed as an afternoon snack but there are no rigid rules on its consumption. It can be enjoyed with any sort of tea as well.

Hope this is helpful, and please let me know if you have additional questions. Good luck with your project!

Hi.

Im curiouse about their shelf life. If i make them fresh how long can i keep them and where to keep them. I know that bean paste last long but how about the rest? If you can summarize or recommend a site I’d be grateful. Thanks

Hi Renimon20! In the article, I have noted on the shelf life for Namagashi, Han Namagashi and Higashi.

Namagashi = As they are highly perishable, the sweets should be refrigerated and consumed by the next day.

Han Namagashi = They should be refrigerated and be consumed within 5-7 days.

Higashi = The most shelf-stable out of the three, it should be consumed within 1-3 months.