Japanese New Year is the most important holiday of the year in Japan. We bid farewell to the past year and welcome with new year with special foods, traditions, and customs. I’ll share how we celebrate, along with my tips and shortcuts to simplify and adapt the festivities so you can focus on family and good wishes for the coming year.

Quick Overview

As each year comes to a close, families in Japan excitedly prepare for their most festive and important holiday—Japanese New Year (Shogatsu)! The celebratory period is long, starting in December and extends until the official end of festivities on January 11th.

The Japanese usher in a healthy and prosperous new year with symbolic traditions and foods at home, work, school, and temples and shrines.

So, how do we celebrate Japanese New Year at home? In this post, I’m excited to share how the Japanese:

- enjoy special foods, customs, and traditions

- simplify them to make celebrating easy and fun

- prepare throughout the month of December

- bid farewell to the old year on New Year’s Eve

- welcome the new year in the first days of January

Let’s dive in!

What is Japanese New Year – Shōgatsu?

Japanese New Year, known as Shogatsu or Oshogatsu (お正月) is the most important holiday in Japan. It’s celebrated on January 1st, called as Gantan (元旦). Japan adopted the solar (Gregorian) calendar in 1873 during its modernization period, shifting away from the traditional lunar new year.

Oshogatsu is filled with meaningful traditions and customs, and preparations begin well before January arrives. In December, families clean their homes, exchange year-end gifts, and get ready for the holiday.

We welcome the New Year with osechi ryori (おせち料理)—beautifully prepared celebratory feast—along with visits to temples and shrines. It’s all meant to welcome a fresh start and good fortune for the year ahead.

What We Eat for Japanese New Year

When I was growing up, we usually spent New Year’s Day with my mother’s side of the family in Osaka. While the men deep cleaned the house, three generations of women—my grandma, my aunts, my mom, and I—gathered in the kitchen all day long over a few days to make the traditional Japanese New Year foods.

Known as osechi ryori (おせち料理), or osechi (おせち) for short, this colorful and deeply meaningful feast is packed into three-tiered boxes called jubako.

A traditional osechi menu may consist of up to 15 dishes or more, and each dish is an edible good-luck charm filled with hopes for the coming year.

- Check out Just One Cookbook’s collection of 17 traditional osechi ryori recipes for your Japanese New Year feast!

Also, we enjoy other customary foods served with, before, or after the big osechi feast. You may know many of these famous and delicious dishes!

- soba noodle soup – toshikoshi soba

- Japanese rice cakes – mochi

- mochi soup – Kanto-style ozoni or Kansai-style ozoni

- sweet medicinal sake – otoso; or serve amazake

- seven herb rice porridge – nanakusa gayu

What We Do for Japanese New Year

Here’s a quick rundown of the traditional customs in Japan leading up to Japanese New Year (JNY) from December through early January.

DECEMBER

In Japan, December is a time of preparation for the New Year. Families, workplaces, and communities spend the month wrapping up the year while preparing to welcome a fresh start.

The month of December is called Shiwasu (師走) in Japanese, and the kanji character literally means “masters/teachers run.” This implies that it’s a hectic time even for typically calm and composed mentors and sensei.

Year-end gifts: Oseibo

At the end of the year, people send out gifts called oseibo (お歳暮) to their managers, customers, and teachers to express appreciation for the entire year. Popular gift items include:

- fresh food (seafood, meat, and fruits)

- condiments

- beer

- tea/coffee

- canned foods

- desserts

- gift certificates

Forget-the-year party: Bonenkai

There are many year-end parties with colleagues and bosses called bonenkai (忘年会), which means “forget-the-year party.”

Companies often have parties from early to late December before shutting down in the final week of December.

The big cleaning: Ōsouji (Dec. 13–28)

People meticulously clean their homes, offices, and businesses from top to bottom during this time. This annual year-end house cleaning tradition is called Ōsouji (大掃除) or “the big cleaning.”

- Eliminate the dirt, dust, and clutter from the past year.

- Welcome the new year with a clean, fresh home and mind.

Rice cake pounding: Mochitsuki (on Dec. 28)

Mochitsuki (餅つき), or rice cakes pounding, is an important annual event usually performed on the 28th, considered an auspicious day.

Traditionally, families steamed glutinous rice and pounded it in a large Japanese stamp mill with a wooden pestle called kine (杵). These days, you can often find mochitsuki events held at temples/shrines and community centers.

- We consume mochi to wish for good health in the new year.

- There is nothing like eating fresh-made mochi—it’s so smooth and springy! Add fresh mochi to Zenzai (sweet red bean soup).

- Make Kagami Mochi—rice cake decoration (see next section).

- Modern option: Use an electric mochi pounding machine or make mochi with a stand mixer!

Japanese New Year decorations (before Dec. 28)

Japanese New Year decorations are displayed to welcome Toshigami, the deity of the New Year, and to pray for good health, happiness, and prosperity in the year ahead. Common decorations include:

- Kagami Mochi (鏡餅)

- Kadomatsu (門松)🎍

- Shimekazari (しめ飾り)

Kagami Mochi – Displayed indoors on December 28, this New Year offering consists of two stacked rice cakes topped with a “daidai” bitter orange. It represents family harmony and longevity.

- Modern option: Find plastic kagami mochi (filled with individually packaged rice cakes) sold at Japanese grocery stores in December, or display a ceramic kagami mochi decoration.

Kado Matsu – Traditionally made with pine branches and angled bamboo stalks, these New Year decorations are placed at entrances or gates to guide the New Year deity to the home. They symbolize longevity, strength, and prosperity.

- Modern option: Simplify with mini-kadomatsu decorations found at Japanese shops and supermarkets, or create your own creative pine and bamboo arrangements.

Shimekazari – Hung on front doors, gates, or near household altars, this New Year decoration is made from sacred straw ropes (shimenawa) to welcome the New Year deity and protect the home from misfortune.

- Modern option: Simplify with mini-shimekazari decorations found at Japanese shops and supermarkets, or create your own creative pine and bamboo arrangements.

When to Display and Remove Decorations

- Put up New Year decorations by December 28.

- Many people avoid decorating on December 29, as the number 9 is associated with bad luck.

- Take decorations down after Matsunouchi—January 7 in eastern Japan and January 15 in western Japan. They are often returned to shrines to be burned in a ceremonial ritual.

Prepare New Year feast: Osechi ryori (Dec. 27–Jan. 1)

We typically cook osechi dishes in the last four days of December, ending on the morning of January 1st. However, the organizing, planning, and grocery shopping start weeks earlier!

Nami’s Tip:

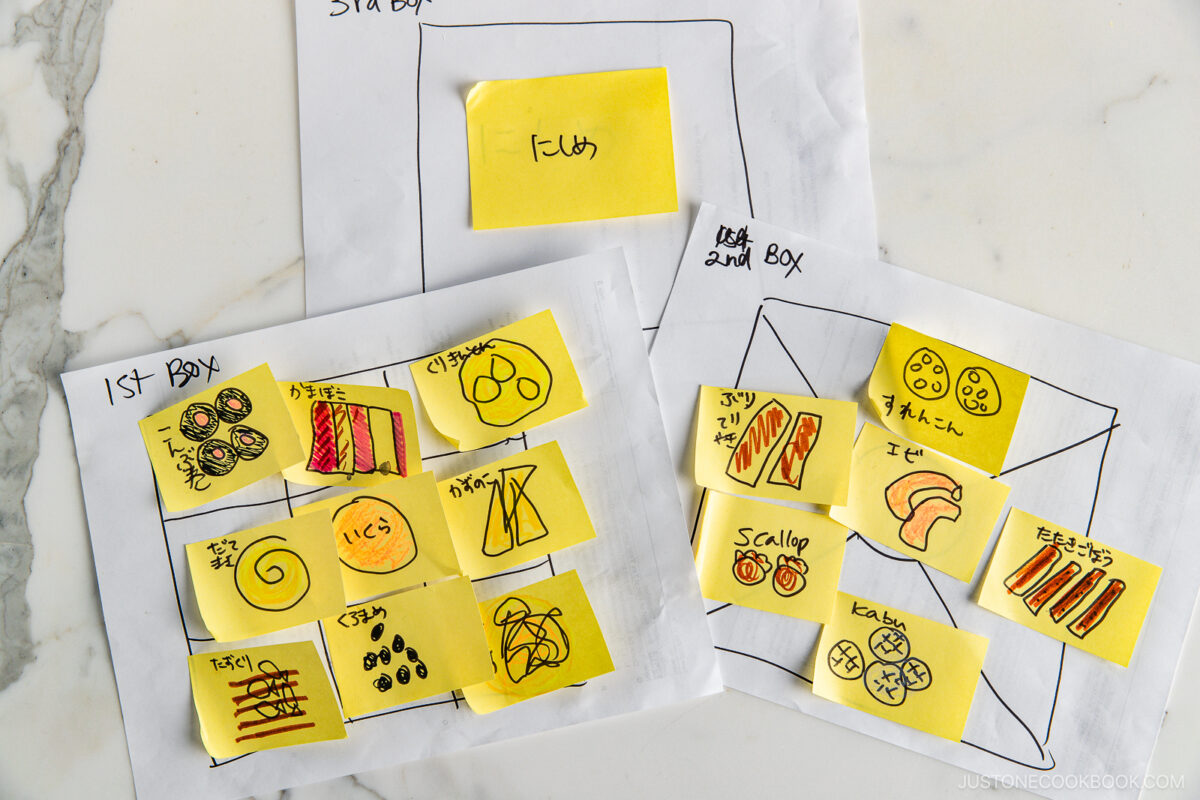

- Stay organized and on track with my 5-day Osechi Cooking Timeline and bonus 4-week schedule of tasks.

- If you decide to use a traditional jubako, see my helpful tips on how to plan and how to pack osechi ryori in 3-tier boxes.

NEW YEAR’S EVE: Ōmisoka

The Japanese usually celebrate New Year’s Eve—called Ōmisoka (大晦日)—and New Year’s Day with family. I feel this holiday is equivalent to American Thanksgiving.

Enjoy New Year’s Eve dinner

Each family has its own traditions for New Year’s Eve dinner. Growing up in Japan, I remember my family often preparing temaki (sushi hand rolls) or sukiyaki as our final meal of the year.

The most popular menus are:

- Sushi – like Temaki Sushi (Hand Roll Sushi)

- Sashimi

- Japanese hot pot – like Sukiyaki, Yosenabe, and Shabu Shabu

In some regions of Japan, people even start eating osechi ryori on New Year’s Eve!

Watch an annual NYE show: Kohaku Utagassen

At night, many people enjoy watching a popular music contest broadcasted by NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) called Kohaku Utagassen (紅白歌合戦).

It’s a live singing contest between the red team (female singers) and the white team (male singers). The participants include young J-pop singers as well as Japanese ballad enka singers. At the end of the show, the audience cast their votes for the red or white team.

Enjoy “year crossing over” noodles: Toshikoshi soba

Before the year ends, the Japanese must eat soba noodle soup in the Toshikoshi Soba (年越し蕎麦) tradition.

- The long, thin buckwheat noodles symbolize longevity.

- My family snacked on small bowls of soba while watching the singing contest.

Did you know?

At any time before 11:59 PM on December 31st, the Japanese say, “Yoi otoshio!“ (良いお年を), which means “Have a nice year!”

Until then, we will not say “Happy New Year!”

Listen to temple bells: Joya no kane

As far as midnight traditions go, the Japanese stay up until midnight to listen to the 108 chimes of temple bells, which we call joya no kane (除夜の鐘).

- Temples throughout Japan ring their big bells 107 times just before midnight and once after midnight.

- It’s a Buddhist belief that this helps people get rid of evil passions and desires, purifying their hearts for the upcoming year.

After the stroke of midnight, we finally say “Akemashite omedeto (gozaimasu)!“ (明けましておめでとうございます), which means “Happy New Year!”

NEW YEAR’S DAY: Oshogatsu

In Japan, the New Year’s celebration typically lasts for the first three days of the year. January 1–3 is a national holiday in Japan, and most businesses shut down. Families typically return to visit their hometowns and spend these few days together.

View first sunrise: Hatsuhinode

We call the first day of the new year Ganjitsu (元日), and many people wake up early and go to a scenic spot to greet the first rising sun, Hatsuhinode (初日の出). Shrines often offer free amazake for good health and fortune during the first visit of the year.

Enjoy New Year’s feast: Osechi ryori

On the morning of January 1st, we arrange the osechi foods in a two- or three-tier box called jubako (お重箱). The family then gathers (brunch for us) to enjoy this most important and symbolic meal of the year.

Enjoy mochi soup and sake: Ozoni and otoso

The Japanese enjoy mochi, drink sweet medicinal sake called otoso (お屠蘇), and eat mochi soup called ozoni (お雑煮) as accompaniments to the osechi meal.

There are two main regional varieties of this popular and hearty rice cake soup:

- Kanto-style Ozoni with clear soup from Eastern Japan (Tokyo area)

- Kansai-style Ozoni with miso soup from Western Japan (Osaka area)

Open greeting cards: Nengajō

After the meal, the family gathers to read nengajō (年賀状), New Year’s greeting cards specially marked for delivery on January 1st. Nengajō often features the Chinese zodiac animal for the New Year, with each year represented by a different animal.

- In December, most stationery stores in Japan sell pre-printed nengajō (年賀状) with seasonal designs.

Give monetary gifts for children: Otoshidama

Children look forward to receiving otoshidama (お年玉) on New Year’s Day. Parents, relatives, or acquaintances present this monetary gift in a small traditional envelope.

- In December, you can find these money envelopes (お年玉袋 and ポチ袋) at most stationery stores in Japan and at Japanese supermarkets outside of Japan.

Play traditional games

There are a few games that the Japanese traditionally play on New Year’s Day.

Some of my favorites are:

- Japanese badminton with a wooden rectangular racket called hanetsuki (羽根つき)

- Kite flying called takoage (凧揚げ)

- Card game called karuta (かるた)

FIRST DAYS OF JANUARY FESTIVITIES

First temple/shrine visit: Hatsumode (Jan. 1–3)

During the first three days of the New Year, the Japanese also visit a shrine or temple to pray for happiness and good luck in the coming year. Called hatsumōde (初詣), this tradition has been deeply ingrained in Japanese culture for centuries.

- Shrines like Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine (明治神宮) attract over 3 million visitors over three days.

- Most people dress casually, though some visitors enjoy wearing kimono (着物) to celebrate the New Year.

- Visitors buy a good luck charm called omamori (お守り) at the temple for protection from illness, accidents, and disasters.

Enjoy hanabira mochi (month of January)

Once the New Year begins, we buy blush pink confections called hanabira mochi (花びら餅). These half-moon shaped mochi are only available in January and served at the first tea ceremony of the new year.

- Sweetened pieces of burdock root protrude from both sides, with white miso in between.

- It’s a simplification of hagatame no gishiki (歯固めの儀式) or “teeth hardening ceremony” from the Heian period (794–1185).

- We eat it to wish for a healthy and long life (with good teeth!)

Enjoy 7-herb rice porridge: Nanakusa gayu (Jan. 7)

On January 7th, the Japanese observe a tradition known as Nanakusa no Sekku (七草の節句), or the Festival of the Seven Herbs. We eat a soothing rice porridge called nanakusa gayu (七草粥).

- It’s believed to bring good health and ward off evil spirits in the new year.

- Mild and comforting, it allows our stomachs to recover from the New Year feasts.

- It’s quick and easy to make Nanakusa Gayu at home!

“Open the mirror”: Kagami biraki (Jan. 11)

To conclude the Japanese New Year celebrations, kagami biraki (鏡開き) is typically held on January 11th. This ceremony literally means “opening the mirror” or breaking of the mochi. Here’s how we do it:

- Remove the round-shaped mochi from the family altar.

- Break them into smaller pieces with a wooden mallet or your hands.

- Cook them in dessert or soup like Zenzai.

- Symbolizes a prayer for health and good fortune.

FAQs

How do you celebrate JNY at home?

Here in the United States, we enjoy a family dinner on New Year’s Eve and snack on small bowls of soba noodle soup to wish for longevity. On New Year’s Day, we enjoy a feast of Japanese New Year foods called osechi ryori and mochi soup called ozoni.

What foods are eaten for Japanese New Year?

We eat deeply meaningful Japanese New Year foods called osechi ryori that symbolize all the wishes and hopes for the coming year like good future, good health, and prosperity. We enjoy other customary foods around this holiday like toshikoshi soba, ozoni (mochi soup), mochi rice cakes, zenzai, and seven-herb rice porridge.

What is osechi ryori and what does it mean?

Japanese New Year foods called osechi ryori may consist of up to 15 dishes or more, and each dish is an edible good-luck charm filled with hopes for the coming year. The osechi tradition started more than 1,000 years ago as a special offering to the gods. Eventually, it became the New Year feast that everyday families enjoy today.

What is toshikoshi soba and when do you eat it?

Before New Year’s Eve ends, the Japanese eat soba noodle soup in the Toshikoshi Soba tradition. These long, thin buckwheat noodles symbolize longevity.

Now that you have learned how the Japanese celebrate New Year, I hope you can add some of our traditions, customs, and foods into your own festivities, no matter where in the world you live.

As a Japanese living in the United States, I hope the spirit and good wishes of Japanese New Year will continue with future generations.

Happy New Year!

Yoi Otoshi O! 良いお年を!(before January 1)

Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu! 明けましておめでとうございます!(after January 1)

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published on December 29, 2015. It was updated on December 30, 2022, and republished on December 26, 2025.