Discover the world of Japanese cuisine, or Washoku (和食), and its place in Japanese history, geography, and culture.

Sushi (寿司), Tempura (天婦羅), Ramen (ラーメン). What comes to mind when you think of Japanese cuisine?

The three dishes above are irrefutable and iconic, so recognizable that each has its emoji! But did you know they are recent creations from the last few hundred years? You may be familiar with nigiri sushi, which began as a popular street food during the Edo period (1603 – 1868).

Another street food, tempura, was initially brought by Portuguese traders and missionaries in the 16th century. And ramen came from China in the early 20th century, a favorite among blue-collar workers in the post-war era. Despite Japan’s long history, tracing back to 10000 BC, many famous Japanese dishes known abroad are relatively new.

So then, what is a “traditional” Japanese dish? What is Washoku (和食)? What makes Washoku so unique that it was designated as an Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO? Let’s take a short tour around the elements of Japanese cuisine, AKA Washoku.

What Is Washoku?

Another name for Japanese cuisine is “Washoku” 和食, where 和 means ‘Japan’ or ‘harmony,’ 食 means ‘food’ or ‘to eat.’ As implied in the kanji (漢字; Chinese characters), Washoku harmoniously blends the ingredients for a nutritious and beautifully presented meal.

The key features of washoku include:

- Balance and Harmony: Washoku balances flavors, colors, and textures. It incorporates the five basic tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami.

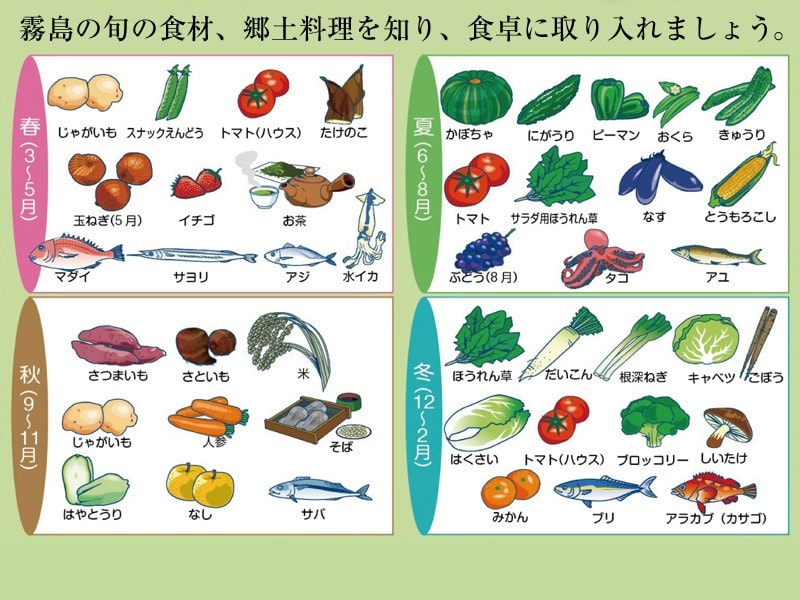

- Seasonality: Ingredients are chosen based on their seasonal availability, known as “shun.” Seasonal foods, such as vegetables, fruits, and seafood, are believed to be at their peak flavor and nutritional value (more below).

- Presentation: Aesthetic presentation is highly valued. Meals are often arranged to be visually appealing, and great care is taken in selecting serving dishes and utensils.

- Techniques: Washoku employs various cooking techniques, including raw preparations , grilling, steaming, simmering, and deep-frying. Each method is chosen to enhance the natural flavors of the ingredients.

- Rice as a Staple: Japanese short-grain rice is a fundamental component of washoku and is often served with every meal. It is considered the main source of energy for the Japanese.

- Use of Fresh and Local Ingredients: Washoku emphasizes using fresh, local, and seasonal ingredients. This reflects a connection to the natural environment and an appreciation for regional flavors.

- Ceremonial Aspects: Washoku can extend beyond the actual meal to include traditional dining etiquette and celebratory dishes.

The term is a recent creation from the Meiji period (1868-1912), the beginning of Japan’s modernization and industrialization from the feudal era. Until then, contact with foreign countries was severely restricted under the Tokugawa Shogunate. As Japan opened its borders, an influx of new cultures (and food!) arrived from European nations and the U.S.

The consumption of beef and pork, once considered taboo by Buddhist practice (but secretly consumed throughout centuries), quickly spread among the Japanese and fusion dishes such as Nikujaga (肉じゃが), Curry (カレー), Tonkatsu (トンカツ), and Croquette (コロッケ) were born.

To distinguish traditional Japanese cuisine from exotic Western cuisine (西洋料理) and western influenced Japanese cuisine called Yoshoku (洋食), the term Washoku was cooked up.

Looking at a map of Japan, it’s easy to imagine how Japan’s geography influences its cuisine. The country’s archipelago stretches over 3,500 islands, from the snowy northern island of Hokkaido to subtropical Okinawa. With over 18,000 miles of coastline and 70 percent of the country covered by mountainous terrain, the cuisine features plentiful abundance from the “fruit of the sea” (海の幸) and “fruit of the mountains” (山の幸).

The Four Seasons

The four distinct seasons also play a crucial role in Japanese dishes. While the changing seasons are not unique to the country, the seasonal cycle is deeply infused in Japanese culture, displayed in traditional arts, poetry, dress attire, and cuisine. This respect for nature’s cycle can be seen in Shun (旬; “season”) when produce reaches its peak flavor and nutritional value.

This seasonal awareness of the cuisine is one of the defining aspects of Washoku.

Examples are plump green peas and hamaguri clams in the spring, spicy shishito peppers and Japanese whiting in the summer, woody matsutake mushrooms and pike eel in the fall, and herbal shungiku greens and buri yellowtail in the winter.

Rice also has its shun, known as shin-mai, or newly harvested rice (新米). It is prized for its characteristic moist and tender texture, only available for a short window. During this time of year, you will see supermarkets displaying bags of shin-mai.

You may also see seasonal motifs painted on plates and bowls at kaiseki restaurants. For example, you may notice a little sprig of tender green leaves or a vivid red maple leaf adding color to the dish.

Washoku: UNESCO Designation

In 2013, UNESCO designated Washoku as the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Washoku was applauded for its “social practice based on a set of skills, knowledge, practice, and traditions related to the production, processing, preparation and consumption of food…[and] respect for nature that is closely related to the sustainable use of natural resources.” (UNESCO).

Washoku joined other famous cuisines on UNESCO’s list, including French cuisine, traditional Mexican cuisine, and the Mediterranean diet.

While the UNESCO designation recognizes the importance of the history of Japanese cuisine, it doesn’t hold it back from evolving. Similar to how Yoshoku became a part of Washoku, Japanese cuisine, and the Japanese appetite are continuously changing and integrating new cuisines. With the boom of Japanese cuisine abroad, like teppanyaki, sushi, ramen, and matcha, and the steady flow of incoming tourists seeking a delicious meal and experience, it’s exciting to think what Japanese cuisine will look and taste like.

Experience Washoku in Japan

You may hear about different styles of multi-course Japanese meals – ending with Ryori (料理) – which translates to cooking/cookery/cuisine. If you’re seeking a fancy washoku meal during your travels in Japan, try out one (or more!) of the following:

- Shojin Ryori 精進料理 – Popularized by Zen Buddhism, Shojin Ryori refers to entirely vegan temple food (although some temples allow milk products).

- Cha-Kaiseki Ryori (also referred to as Kaiseki Ryori) 茶懐石料理 – A meal served before a Japanese tea ceremony. Originally, Cha-Kaiseki Ryori was a frugal meal to satisfy hunger pangs before the ceremony.

- Kaiseki Ryori 会席料理 – Same pronunciation as above, but different Chinese characters. Kaiseki Ryori refers to a meal traditionally served at ceremonial banquets. There are Kaiseki restaurants, which you can read more about on JOC from Nami’s Kaiseki experience in Kyoto, Hida Takayama, and Den in Tokyo.

- Honzen Ryori 本膳料理 – A formalized meal from court aristocracy, served on legged trays. Although rarer these days – replaced by tables and chairs – some places still offer a true Honzen Ryori experience.

Learn more about Washoku and Japanese Food Culture

- Kaiseki Ryori: The Art of the Japanese Fine Dining

- Plan a Japanese Meal: One Soup Three Dishes “Ichiju Sansai” (一汁三菜 )

- Yoshoku: The Japanese Adaptation of Western Cuisine

- Japanese Dining Etiquette 101 食事のマナー

- Baby Food in Japan

- Nutrition and Food Education in Japan

I recommend the following books for those curious to read more about Washoku.

- Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art by Shizuo Tsuji

- Introduction to Japanese Cuisine: Nature, History and Culture by the Japanese Culinary Academy

- Japanese Farm Food by Nancy Singleton Hachisu

- Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen by Elizabeth Andoh

Do you have any recommendations that sparked your curiosity? Please share in the comment box below!