Japanese babies are introduced to rice, dashi, tofu, and fish at an early age. Learn all about baby food milestones in Japan and what the Japanese feed their very hungry little ones.

Have you wondered what Japanese parents feed their tiny tots? Hint: it’s not 🍣 or 🍤 or 🍜! Then, what are some of the first foods that Japanese babies eat?

Hello there, I’m Kayoko. I’m a contributing writer for Just One Cookbook based in Tokyo and a mother to an almost 2-year-old daughter.

Like many new parents, when the time came to transition to solid food, I searched high and low for information regarding the bewildering new world of baby food.

My Own Baby Food Experience

You might be reading this because you’re about to start the solid food journey with your baby and are interested in introducing Japanese food to her/him. Or just a curious reader! You’re not alone; we have received so many requests for Japanese baby food in the past like this:

Hi, JOC!

I have a hungry toddler and I’ve been wondering what babies and children in Japan eat on a day-to-day basis. I adore Japanese food and your homestyle dishes but when I offered them to my child, he wasn’t too thrilled with the new foods.

I’d love to find out more about what Japanese parents feed their children and if I can incorporate some dishes to his meals. Thanks!

-L.L. (a JOC reader)

Through my research and findings, it was fascinating that the information regarding baby food in Japanese and English (primarily U.S.-based) was starkly different. This includes cultural practices, messaging, and the varieties of food offered.

For instance, many baby food sources in the West list avocado, mango, nut butter, and fortified cereals as introductory foods for babies. Baby-led weaning (BLW) is well-known, and many resources exist. However, as you’ll soon learn, Japanese babies are fed Japanese foods like rice, tofu, and dashi from an early stage. Most Japanese parents spoon-feed their babies these foods until they can use utensils much later.

Although I cannot compare with parents outside of Japan, I’d like to share my experience introducing solids to my daughter and baby food in Japan. Remember that this is just one parent sharing her observations and discoveries, so I hope you enjoy learning about the different cultural aspects.

💁🏻♀️ Please note that I am not a nutritionist, dietician, or expert in the field of baby food. For those who wish to introduce Japanese foods to your baby/child, please do your research, vet your sources, and consult your pediatricians.

Japan Baby Food Information

In this post, I’ll cover:

- Japanese Baby Food Guidelines

- Basic Japanese Food Given to Babies

- Japanese Baby Food Stages

- Japanese Foods Not Suitable for Babies

Japanese Baby Food Guidelines

It is impossible to make a fair comparison of baby foods worldwide; however, through my research, I found several aspects exciting and perhaps unique to Japan.

1. Clear guidelines from the government

Baby food in Japanese is called Rinyushoku (離乳食; literally “food separated from milk,” refers to food given to a baby between 5/6mo to 18mo). In Japan, babies typically begin eating solids after the 5-6 month checkup.

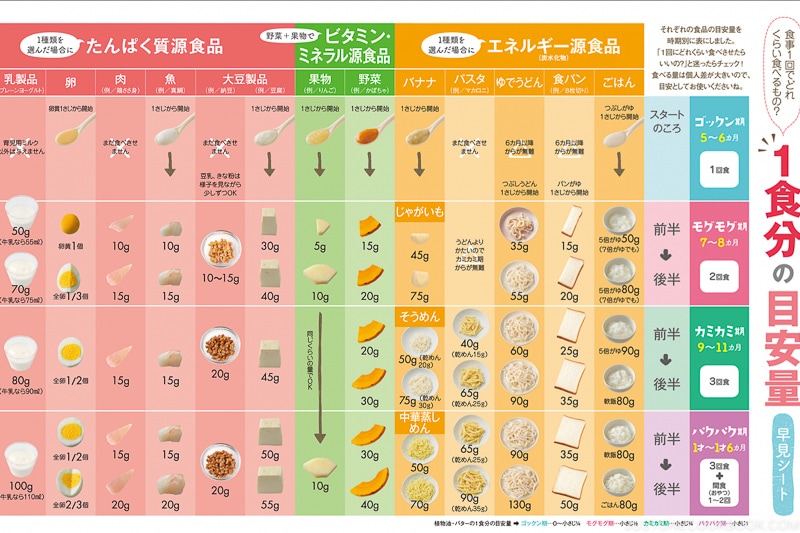

Information regarding Rinyushoku is primarily based on the guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW). It is established by a board of doctors, healthcare providers, and registered dieticians. The guidelines range from the size and softness of the cooked vegetables to the thickness of the rice porridge when certain foods can be given to the baby… it’s pretty specific!

For the most part, regardless of what baby food recipe book you pick up, you won’t find conflicting information regarding types of food and the stages given. Because of this consistency, most parents and childcare facilities follow these guidelines (MHLW 2019 info in Japanese).

Other non-MHLW-approved baby food practices have slowly gained traction in Japan among some parents and pediatricians. Notably, baby-led weaning (BLW) is the practice of babies self-feeding finger foods rather than being spoon-fed (I did a mix of purees and BLW). There are some books and resources in Japanese, but most babies are spoon-fed initially until they move on to more solid foods and can use utensils.

2. Emphasis on introducing Japanese food

Similar to other countries, babies are exposed to the traditional/native cuisine of their culture at an early age to build an appreciation for their cuisine later in life.

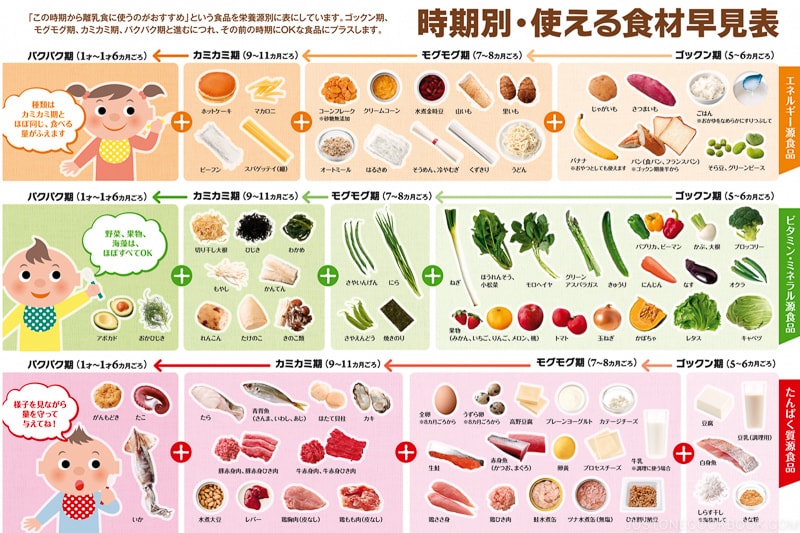

In Japan, babies are given rice, tofu, natto, seaweed, dashi, sweet potato, and other Japanese ingredients at an early stage. Parents then gradually incorporate more foods and dishes into a simplified Ichiju Sansai meal around two years old.

3. Pressure to make baby food from scratch

Perhaps this is a universal headache parents feel worldwide, but there is tremendous pressure to prepare baby food from scratch! While there is a diverse and affordable selection of ready-made baby foods, most Japanese baby food cookbooks feature labor-intensive recipes of pureeing, straining, mashing, and grinding meats and vegetables by hand.

Many cookbooks emphasize that preparing baby food from scratch is an act of love during a relatively short period of a child’s life. This may be true, but it is quite the hurdle for any parent whether s/he is additionally balancing work. A 2016 poll of Japanese guardians by the MHLW found that 33.5% of responders said that their top concern regarding baby food is preparing it. Talking to friends with children, many said they struggle to feed their children nutritious, homemade baby food without overburdening themselves with all the cooking.

As for Japanese pre-made baby foods, the food companies must align with the guidelines of the MHLW. They undergo rigorous screening and must label their products according to the appropriate months. These baby foods are available in powdered, freeze-dried, retort pouches and containers for easy prep. They tend to be free of additives, fragrances, and artificial colors and have food allergies listed in the package.

Despite its wide availability, I felt a slight twinge of guilt picking up a few pre-made meals for convenience. Many cookbooks help you meal prep for the week. However, I found that a mix of store-bought baby foods and homemade food was a healthy balance for me and my baby. I heavily relied on my hand blender and stocked the freezer with purees and different textures of foods.

4. Resources for baby food

When researching baby food in the U.S., I noticed many excellent resources by registered dieticians and feeding specialists. This information is shared on their websites, Instagram accounts, or paid seminars (I relied on @feedinglittles, @solidstarts, and @newwaysnutrition).

While these extraordinarily qualified and tech-savvy individuals provide a tremendous amount of quality research-based information, I found it curious that U.S. government agencies weren’t actively promoting their resources on baby food (there are some, as this page by the U.S. Department of Agriculture). It seemed like most parents were off to find reliable information. Of course, in a multicultural and diverse country like the U.S., a blanket guideline that considers all the various food cultures and observances would be near impossible. It makes sense that parents seek information that suits their family’s and babies’ needs.

In Japan, it’s a stark contrast with an abundance of books on baby food, most following the MHLW guidelines. Plus, many pediatrician clinics, local municipal offices/wards, and NPOs offer seminars and workshops for new parents (in person or online, and most are free!) to learn more about baby foods.

When my daughter had her 5/6 month checkup at our ward office, the pediatrician gave us a booklet of baby food recipes and directed me to a link to online classes if interested. I picked a baby food cookbook at the bookstore and mostly followed along.

Basic Japanese Foods Given to Babies

So, what do we feed babies in Japan? I’ll stick to the 5-month to 18-month period when babies experience their first taste of Rinyushoku. Once the baby graduates from Rinyushoku, the next step is called Youjishoku (幼児食; literally “toddler food,” refers to foods post-Rinyushoku up until around five years old).

Babies are exposed to various Japanese and non-Japanese foods through their baby food journey. In this article, I’ll be focusing only on Japanese food.

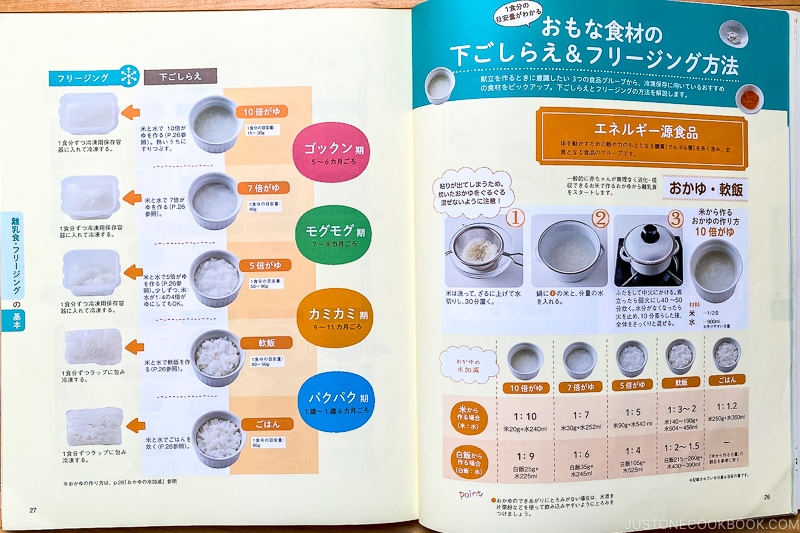

1. Rice

No price for guessing this right: a Japanese baby’s very first food is white rice. It is our number one staple food, after all. Rice is easily digestible, versatile, and affordable, and rice allergens are relatively uncommon. Babies are first given a watery rice porridge called Jubai Gayu (10倍粥; literally “ten times rice porridge,” which is white rice cooked with ten times the amount of water). Then, gradually given less watery porridge over the next several months.

This porridge can be made by adding extra water when cooking rice in the rice cooker. Or microwaving cooked rice with water and grinding it to a smooth paste. It’s also available in powdered form, which must be reconstituted.

2. Dashi

Babies are given small amounts of dashi (Japanese soup stock) to add some flavor to purees and rice porridge. Made with water steeped in kombu seaweed and sometimes bonito flakes, dashi is preferred over salt, soy sauce, or miso because of its low sodium content. A bit of dashi adds a taste boost to the food, especially for babies learning new flavors. It’s also used to thin out purees.

As powdered dashi tends to have additives and a lot of salt, homemade dashi, whether fish-based, mixed, or vegan (kombu or shiitake), is recommended. You can also find low-sodium dashi packets suitable for babies. Leftover dashi can be frozen in ice cube trays for easy use next time.

Dashi can be given to babies in the early 5-6 month period.

3. Soybean Products (Tofu, Natto, etc)

Tofu, natto, koyadofu, and other soy ingredients such as kinako, soy milk, and yuba (dried tofu skins) are excellent plant-based protein sources. Silken tofu can easily be crumbled up for easy spoon-feeding. Once the baby can eat more solid foods, s/he can transition to firm tofu cut into cubes, which can be picked up with a fork or fingers.

Ground-up koyadofu and kinako can be sprinkled on top of purees, yogurt, and rice porridge. If the powders are mixed into wet foods, they can be served in the early 5-6 months.

Natto (fermented soybeans) is a Japanese superfood that provides a good source of probiotics. And yes, it is known for its sticky, slimy texture and pungent smell that many foreigners describe as smelly cheese. Since it requires an acquired taste, the Japanese know it’s best to introduce natto to babies as early as possible. Natto can be served as is or chopped up and snuck into rice porridge or purees. There is also finely chopped natto called Hikiwari Natto (ひき割り納豆), which is available wherever natto is sold.

We leave out the soy sauce-based seasoning and mustard as they are high in sodium. If the smell puts your baby (or you) off, pour hot water over the natto and drain well. That should remove some of that funkiness.

My daughter has loved natto from the first day we served it to her, and she prefers to eat it as is, which was picking up the beans with her fingers and smearing it all over her face (cue in the eye-rolling and the messy cleanup afterward).

For older babies, we also serve fried tofu such as atsuage and aburaage by draining the oil out with hot water and chopping it into manageable pieces.

4. Japanese Noodles

The Japanese love noodles just as much as rice, so naturally, we start serving wheat-based noodles such as udon and somen noodles to our babies in the early 5-6 month period. We would cook the noodles until they soften and chop them into tiny pieces for easy digestion.

Dried noodles have salt added to extend their shelf life, so wash and drain the cooked noodles very well. I found somen noodles tricky to serve as the thin noodles clung to everything: the bowl, clothes, hair, basically everywhere! Udon was much more manageable; my daughter could pick the cut noodles with her fingers.

Soba noodles are made with buckwheat, which is a known food allergen. Just be cautious when serving.

5. Non-Caffeinated Tea

Not a food, but non-caffeinated tea such as mugicha (麦茶; barley tea) is a popular drink often served to babies, usually when they start solids. There are mugicha tea bags and drink packets for babies and little children.

Since mugicha is naturally non-caffeinated, regular mugicha packets will also suffice. I always have a pitcher of mugicha in the fridge year-round and would pour a glass for my daughter during mealtimes or pour it into her water bottle whenever we went outside. Of course, tea should never be served as a replacement for breast milk/formula.

Other types of Japanese tea that can be served to babies and children are green tea and hojicha, although make sure to look for non-caffeinated varieties.

Japanese Baby Food Stages

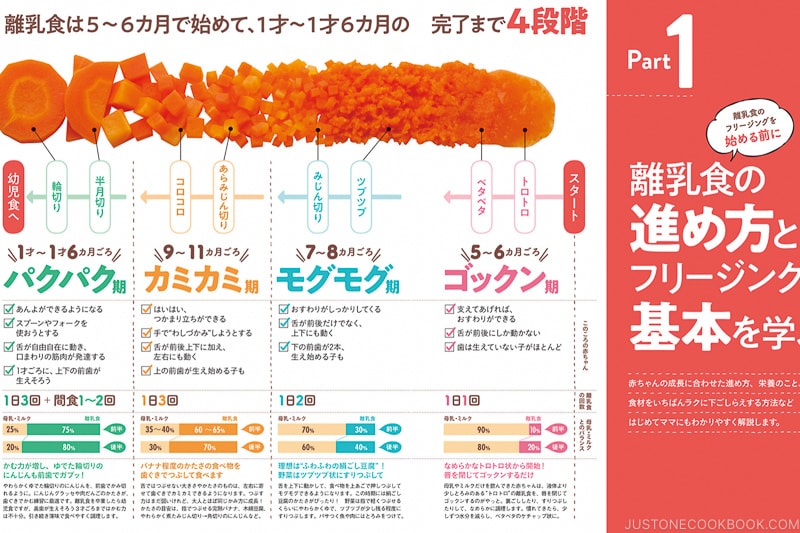

The MHLW guidelines divide the baby food stage into four sections, starting at the 5-6 month mark until the baby “graduates” at 18 months.

Stage 1: 5-6 Months

An example menu I fed my daughter

- Okayu (Jubai gayu 十倍粥)

- Udon or somen noodles, cooked until soft and chopped up into tiny pieces

- Finely crumbled silken tofu

- White fish such as cod, sea bream, or flounder steam cooked, then mashed up and thinned with dashi

- Vegetable purees such as tomato, pumpkin, carrot, daikon, komatsuna, taro root, and napa cabbage

Like in many cultures, the first stage of baby food is all about purees and soft foods. As mentioned above, a baby’s first food is white rice, which s/he will continue to eat with a spoonful for the first few days. The portions tend to be small and given once a day, as the primary source of nutrition still comes from breast milk/formula.

Other purees such as vegetables, cooked white fish, and crumbled silken tofu are commonly fed to babies during this time. Besides rice, starches mashed or finely chopped, such as udon and somen noodles cooked very well, white bread, oatmeal, potatoes, and taro root can also be fed.

I served rice porridge and the vegetable/protein dish separately but merged the two dishes for a donburi-style meal for easy prep.

Stage 2: 7-8 Months

An example menu I fed my daughter

- Okayu (Nanabai gayu, 七倍粥, literally “seven times rice porridge,” rice that’s cooked with 7 times the amount of water) with chopped natto

- Canned tuna flakes mixed with diced cooked vegetables and dashi

- Cubed silken tofu

- Soup made of pureed kabocha and soy milk

The 7-8 month period is characterized by the baby’s ability to chew with her/his gums, close the lips, and swallow, so the foods transition from purees to diced foods. Parents usually give the baby two meals a day to start building a mealtime routine.

As I did a mix of spoon-feeding and BLW, mealtimes were messy. But thanks to the constant cleaning after mealtime, our dining table and floor were always (near) spotless!

Stage 3: 9-11 Months

An example menu I fed my daughter

- Lightly seasoned and chopped yaki udon

- Egg omelet with steamed fish flakes

- Ground chicken patties with natto and chopped vegetables

- Boiled unsalted edamame chopped up and mixed with yogurt

By this period, babies are able to chew soft foods similar to a ripened banana texture. Parents usually transition their baby to 3 meals a day, where they get most of their daily nutrition from foods instead of breast milk/formula. They may also be more adventurous to eat with a fork, spoon, or hands.

My daughter was a ravenous eater, so we didn’t have any difficulty feeding her 3 times a day, but some of my friends struggled with uninterested babies, and stuck with 2 meals.

Stage 4: 12-18 Months

An example menu I fed my daughter

- Small onigiri (rice cooked normally) wrapped with nori

- Miso soup (lightly seasoned with miso)

- Tamagoyaki with diced broccoli and onion (no seasoning)

- Kinpira gobo (very well cooked, lightly seasoned, and with no chili peppers)

- Spinach ohitashi

By this time, many mothers have stopped breastfeeding/giving formula and are feeding similar foods that the rest of the family eats with less seasoning. The food should be soft enough to be crushed with the back of a spoon.

I enjoyed serving our daughter the same food we were eating (added more spice and flavor in our portions) as not only was it so much easier than prepping food just for her but because she seemed so much more interested in what we were eating and would try to snatch food off our plates. It seemed like she was learning about the communal aspect of eating!

Japanese Foods Not Suitable for Babies

Babies’ immune system is delicate; their teeth and jaws are still developing, and thus, they cannot quickly process many foods that older children and adults can eat. Here are some foods that should never be served to babies.

Mochi

The sticky, chewy texture of mochi is a choking hazard and should never be served to babies and young children. Most parents wait until at least three years old when the child has grown all her/his baby teeth and can properly chew and swallow food. Mochi is a hazard; there are unfortunate cases of suffocation from eating mochi by young children and the elderly every Japanese New Year. Even if you cut the mochi into tiny pieces, the stickiness can lodge into their tiny throats, so wait until they are older to enjoy it safely.

Similarly, mochigome (glutinous rice) and anything made with it (including Sekihan) should be avoided altogether.

Brown Rice

While brown rice is nutritious compared to white rice, it is highly fibrous and challenging for babies to digest. Even if cooked into rice porridge, the hard hull will remain. Therefore, it’s best to give white rice.

Sashimi and Raw Seafood

Any raw seafood, even sashimi-grade quality, is not suitable for babies. Not only is the texture difficult for babies to chew (think octopus, squid, shrimp, and shellfish), but the risk of parasitic infections and food poisoning is not worth the potential rush to the hospital. While the MHLW and other agencies do not give an exact age when raw seafood can be safely consumed, most parents wait around 3-4 years.

Sushi with cooked toppings such as boiled shrimp, unagi, and vegetables can be served to toddlers, but babies should skip it.

Shirataki and Konnyaku/konjak

Shirataki noodles and konnyaku/konjac are products made of yam plants. The texture is rubbery and difficult to chew, so they should be avoided during the baby stage, even if cut into manageable pieces.

Seasoned Nori, Tsukudani, and Tsukemono

Seasoned nori, tsukudani, and tsukemono are common rice accompaniments in Japan. However, due to the high sodium content, they should be avoided altogether. Unseasoned nori is fine, although it can stick to the roof of the mouth, so it should be given with caution. In the early stages, you could serve shredded nori mixed into rice porridge or cooked rice for easy consumption.

I hope this gave you an insight into what Japanese baby food is like. Although I only touched upon one aspect of Japanese baby food, babies here are exposed to many non-Japanese foods, such as bread, pasta, oatmeal, cheese, and more!

Again, I am not a nutritionist or an expert on baby food. If you wish to feed your baby Japanese food, please consult your doctor/pediatrician. Ultimately, as the parent, you know what’s best for your baby!

In part 2, I will address some of the questions asked by readers that Nami asked on her Instagram a while ago. If you also have questions, please post in the comment box below!

Thank you so much for this wonderfully written post!

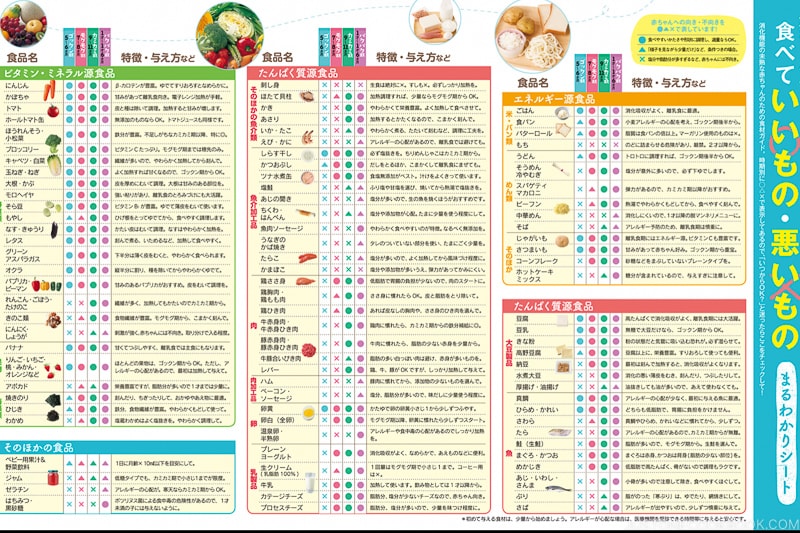

The Japanese guidelines are so specific and visual– and the content is more relevant to me than the westernized resources provided in Canada. It’s good to know there’s an entire country where my values are mainstream.

Hi Stephanie! Thank you so much for reading Kayoko’s post!

We are happy to hear you enjoyed it. 🥰

Hello,

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article. I am living in Japan with two young children and am amazed with the variety of food they eat. Would you be able to share what resources the charts are from? I would like to purchase these books to reference. (My husband can read Japanese)

Hi Gabrielle, thank you for reading 🙂

I don’t remember the titles I referenced, but the books are from around 2020-2021, and so I would recommend picking up the latest edition of the cookbooks for the most updated recommendations. You should be able to find a selection at any bookstore. Good luck!

Is there an english ver.?

Hi, thank you for reading! As I mentioned in the post and other comments, there are no English versions available. None of the baby food books in Japanese are translated and the government website does not offer resources in other languages.

dude every asian country should have a recipe page like this

Hi there, Thank you for reading Kayoko’s post and for your feedback!

We are glad to hear you enjoyed this post!

Thank you so much for this! It’s like you read my mind My daughter is 5 months and interested in everything I eat. She loved the miso soup I had for lunch yesterday and I was wondering what else might be suitable for her. I’m very excited to try her on new and delicious things.

Hi Jessica! Thank you for your comment! I hope your daughter enjoys her food journey and develops a palate for Japanese cuisine!

Hi! I’m Ann from the Philippines.Where I can download or find that book or chat in English version. Thanks!

Hi Ann! Thanks for reading! Unfortunately, there are no English versions available. None of the baby food books in Japanese are translated and the government website does not offer resources in other languages. Sorry I can’t be of much help!

Where can you get the packaged baby food for 7 months old in tokyo and kyoto?

Hi Cat! You can find packaged baby food at most supermarkets, drug stores, and even big-box baby stores (Akachanhonpo, BabiesRUs). Check the label for the appropriate age. Good luck!

Great post!

Wish I had thought of giving natto to my kids when they were small! 😀

Hi Liv! Thanks for reading 😀 Natto is an acquired taste and so it does take time to get accustomed to. Hope your kids like natto!

Hi Nami and crew, I would love to pitch another idea for your website. I was wondering if you could make a list of Japanese condiments safe during pregnancy. I love to cook Japanese food and while our country has a great list of foods which should be avoided, a lot of the Japanese condiments are missing. I would love to know which Japanese condiments and foods are best avoided during pregnancy.

Hi Mieke, thanks for reading! As for your suggestion regarding safe foods during pregnancy, unfortunately as we’re not backed by medical or government agencies, we can only refer to information shared by credible sources.

Here are some sources, if you can’t read Japanese please use the translation feature on google translate: Wakodo (major baby food brand), Moony (major diaper brand). I also found a n old blog post of a blogger sharing her experience with food during pregnancy

This is soooooo helpful!! My baby is 7 months old and we just started increasing the texture for him. I’ve always wondered how Japanese children are used to be fed to grow to live long life, haha! Thank you for this! Just wondering if it’s possible to receive the reference charts in large clear photos? If it’s possible it’ll be amazing! 日本語を読むことができます!

Hi Candi! Thanks for reading, and best of wishes on your baby’s food journey! If you’re looking for more baby food resources and can read Japanese, I would highly suggest buying a book from Amazon JP or Kinokuniya, that’ll give you an overview of the baby food journey in Japan (search for 「離乳食」). There are some online resources by baby food brands such as Wakodo and Kewpie that may be helpful.

Can you help explaining about meal prep in part two ? I found most mother in japan meal prep and freeze their baby meal at least once a week, I’m a busy mom too , so i really need new insight about this, in my country we need to make a four/five nutrient in one dish, carbs + vege protein (like soybean / tofu) + animal protein (chicken/fish etc) + vegetable + fat (butter / oil) it’s really hard to make this everyday while working too..

And does babies in japan eat seasoned meals from first stage?

Hi Vhie. I understand the tremendous task it is to meal prep for your baby, especially when you’re balancing work as well. Unfortunately, recipe testing and menu planning is not my field of expertise. However, I did find a Japanese YouTuber sharing baby food and meal prep in English. This might be insightful for you.

For videos, I found YUCa’s Japanese Cooking to be helpful at giving an insight of what Japanese baby food is like. She posts recipe videos in English from the pregnancy stage, baby and toddler foods. You can also check out recipes on her blog YUCa’s Japanese Cooking. Good luck!

Loved this article! Moved about a year ago to Japan with my, at that time, 8 months old son and 5 years old daughter. Even if we used to cook japanese style food back home in Argentina, the switch to the food here was a challenge. Specially knowing what to buy and how to prepare it 😀

It is wonderful how food education is addressed here, so sharing the knowledge can only make a better world. Hope to read more about this <3

Hi Legui, thanks for reading! Yes, food education is a big part in the education system although it leans heavily on the traditional Japanese diet (for obvious reasons). Adapting to the new environment must have been a huge challenge for you an your children. Please stay tuned to part 2!

What an interesting article. I don’t even have a little one. My daughter is already in her 20s. These charts would have made life easier back then. I enjoyed reading this.

Hi Kae, thanks for reading! These charts and sources does make it so much easier for parents, although my mother said that this is quite new and she didn’t have this much information 30+ years ago when she was raising me and my brother.

Thanks so much for this article. It’s so interesting to read about food habits. I wish I could read the pages from Japan you posted. Looking forward to the next one

Hi sewing princess. It’s very unfortunate that there aren’t reliable sources of baby food in English, but glad I can be of some help. Please stay tuned to part 2!

Thank you for this great article! I am a German nutritionist specializing in nutrient in pregnancy and early childhood and was wondering recently how this topic was approached in Japan.

It looks like the cooking of baby food is much easier on the parent in Germany 🙂 we start with puréed vegetables like carrot or squash and add potatoes, meat/fish, oil and fruit purée over the course of ca. 1 month to make up the lunch meal.

Hi Lisa, it’s so interesting what you are specialising in. I would like to get in touch with you. How may I contact you?

You have mail 🙂

Hi Lisa, thank you for reading! I’m glad you were able to learn what baby food is like in Japan from a nutritionist perspective.

Yes, the Japanese guidelines does seem like a lot of work, but I’m sure it’s the same as in Germany, many parents prepare batches and freeze leftovers for later. We love to adhere to careful planned out instructions, which may seem overwhelming to some.

Just FYI, I deleted your email address you shared for privacy reasons as it seemed like you were able to connect with Julia.