Why is Japanese cuisine healthy? It’s all about the investment in food education to build awareness of one’s health and nutritional habits.

Have you ever wondered why Japanese food is considered healthy? What’s the secret to the Japanese people’s longevity, 87.1 years for women and 81.1 years for men? (compared to 78.8 years and 75.1 years in the U.S., respectively).

Not surprisingly, part of the answer lies in what the Japanese eat and how they learn about nutrition and food education.

Japan Dietary Habits and Food Education

The Japanese traditional meal called Ichiju Sansai (一汁三菜) is a balanced diet of rice, protein (typically fish and tofu), and vegetables, usually eaten three times a day. While the Japanese eat non-Japanese foods regularly and consume more red meat and dairy products than previous generations, this meal provides most of the essential nutrients.

In terms of education, Japanese children are taught healthy, sustainable eating habits and attitudes about food from childhood. Students learn about different seasonal and local produce and how to cook them, among other life skills.

In addition, every public elementary and most middle schools have a school lunch program prepared by certified nutritionists. You may be surprised to learn that students deliver the meals from the school kitchens to the classrooms and serve their classmates.

Beyond Japan’s longest average life expectancy, its globally recognized healthy cuisine and food education program taught at schools is a Japanese philosophy of shokuiku (食育)—”food education.” Shokuiku is an educational philosophy based on a social consciousness to eat well. Embraced by the government, shokuiku programs teach the younger generation the appropriate knowledge of nutrition and food culture.

What’s unique about the Japanese view on nutrition and food education?

Let’s review some factors that make the Japanese view on nutrition and food education unique. They are:

- A balanced meal with Ichiju Sansai

- Ma-go-wa-ya-sa-shi-ii (まごわやさしい)

- Cooking techniques

- School programs on food education

We’ll discuss more in detail below.

Balanced Meal with Ichiju Sansai

As you may know, the Japanese diet is traditionally heavy on fish, vegetables, and soy. When meat is involved, it is cooked with other ingredients to avoid becoming the centerpiece. (Read more about washoku AKA Japanese cuisine here).

Compared to people in Western countries, the Japanese have a low intake of red meat, dairy products, and sweeteners intake. These foods are thought to be linked to low mortality from cancer, heart disease, and obesity (for more on the Japanese diet and nutrition compared to Western countries, please read this scientific paper by Nature).

Fish and seafood are said to be the better protein alternatives to animal meats as they are high in omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 fatty acids have many health benefits, including:

- Maintaining a healthy heart by lowering blood pressure

- Reducing and preventing heart diseases

- Reducing the chance of developing diabetes and combating obesity

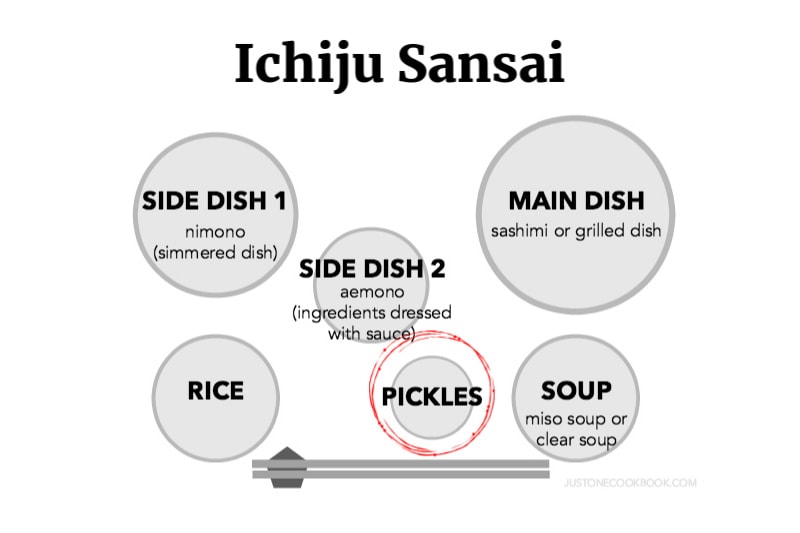

The traditional meal of “one soup three dishes” called ichiju sansai (一汁三菜) provides a balanced meal of essential nutrients. This consists of a serving of rice (approximately 150 g or 5.3 oz), a bowl of miso soup with vegetables and tofu, two side dishes, and the main protein, usually fish.

In addition, the Japanese often incorporate seasonal produce in their meals. It tends to be slightly cheaper and is fresher, tastier, and more nutritious than produce consumed out of season.

Ma-go-wa-ya-sa-shi-ii (まごわやさしい)

To encourage a more plant and seafood-based meal, the phrase ma-go-wa-ya-sa-shi-ii (まごわやさしい) has been in circulation for some time.

It’s an acronym for mame/beans (豆), goma/sesame (胡麻), wakame/seaweed (わかめ), yasai/vegetables (野菜), sakana/fish (魚), shiitake/mushrooms (しいたけ), and imo/potatoes (芋). This phrase also spells out “the grandchild is kind” phonetically.

Not only is this term catchy, but it’s also basically a call to return to the traditional Japanese meal and dietary intake.

So what’s all the fuss about these foods?

- Beans: Also known as “meat of the fields,” beans are high in protein and a bang for your buck. The recommended daily intake is 100-130 g (3.5-4.5 oz) of tofu or one packet of natto.

- Sesame: Includes other nuts such as almonds, chestnuts, peanuts, and ginkgo nuts. Nuts are high in protein, minerals, and antioxidant properties.

- Seaweed: Seaweed, such as wakame, hijiki, and nori are high in calcium.

- Vegetables: Vegetables, especially leafy greens and red and yellow vegetables, are full of essential nutrients. The Japanese Ministry of Labor recommends a daily intake of 350 g (12.3 oz), and American CDC recommends 2-3 cups of vegetables daily.

- Fish: Oily fish such as sardines, mackerel, and anchovies are exceptionally high in essential amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids. These are said to help reduce cholesterol levels.

- Mushrooms: Mushrooms are available year-round and easily incorporated into any dish. They are high in vitamin D, which helps regulate the body’s calcium and phosphate.

- Potatoes: Starchy tubers such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, and yams are high in fiber and vitamin C and aid digestion.

Cooking Techniques

Another reason why Japanese food is healthy is because of the cooking techniques. Most dishes are cooked to preserve their natural colors, flavor, and shapes. In addition, the dishes don’t require long cooking, and thus, the vitamins and minerals don’t seep out.

The most popular and traditional Japanese cooking technique is simmering vegetables or fish in liquid (usually dashi or some combination) called Niru (煮る). This cooking method penetrates the food slowly in low heat and helps incorporate the flavors while retaining shape.

While not eaten frequently, there are deep-fried dishes like tempura and karaage.

Read more about Japanese cooking techniques.

Shokuiku

Shokuiku (食育) – “food education,” is a Japanese philosophy and a governmental policy to enable people to acquire knowledge on food to make proper choices. Encouraging healthy eating habits among individuals would, in turn, address diet and lifestyle-related diseases and enrich one’s quality of life. Enacted in 2005, the Shokuiku Basic Law is a public health program for everyone.

Shokuiku is not a new concept; it was first promoted by Sagen Ishizuka (石塚 左玄; 1850-1909), a military doctor and pharmacist. Educated in Western and Eastern medicine, he promoted a diet rich in sodium and potassium. These minerals help the body to absorb and use other nutrients.

His method, “Shokuyō” (食養, literally “food for health”), encouraged a diet of whole grains and to eat fewer animal products. He also pushed for consuming seasonal and locally grown produce and consuming meals in moderation. He echoed the Eastern philosophy that food sustains life and underlies health and happiness. Not surprisingly, Ishizuka is also known as the founder of the macrobiotic diet.

His concept was quickly popularized during the Meiji era (1868-1912). This was a time of rapid Westernization when the Western wheat, dairy products, and meat diet were embraced to modernize the country.

Incorporate Shokuiku in Your Own Life

So, how can you incorporate the shokuiku principles into your own life? You don’t need a government program or nutritional teachers for a healthy lifestyle!

1. Eat until you’re 80% full

Called hara hachibun-me (腹八分目), “80% stomach,” it’s based on the Confucian teaching where you listen to your body and stop eating before you feel full. This practice can prevent overeating and make you more conscious of your food choices. A Japanese clinical trial on rats found that limiting their food intake instead of letting them eat until full prolonged their lifespan. Therefore, mindful eating will improve your relationship with food for a pleasurable event you partake in daily.

2. Eat whole foods

Sagen Ishizuka was a brown rice fan and discouraged consuming processed foods. Although processed foods are delicious, they are high in unhealthy fats, added sugar, sodium, and calories. Eating whole foods, including skins and whole fish instead of fillets, will nourish you with protein, fiber, heart-healthy fats, and micronutrients. Eliminating your diet from processed foods is difficult in this modern age, but limit your intake.

3. Eat seasonally and locally

Instead of reaching for the same produce available year-round, check out the farmers’ market for fresh local and seasonal fruits and vegetables. You may become more aware of where your food comes from, how it was produced, and what is in season. From juicy tomatoes in the summer to colorful varieties of apples in the fall, you may become more appreciative of the changing seasons!

4. Enjoy your meal with good company

While a grab-and-go meal is a convenient filling method, it diminishes the pleasure of eating. Sharing meals with family and friends builds camaraderie and can help diversify your food offerings. As Aristotle said, “Man is, by nature, is a social animal.”

Food Education at Schools

Your parents may have taught you to eat your vegetables, but what does it mean to teach children how to eat well?

Rather than teaching children through textbook reading and lectures, Japanese schools involve the students. Most Japanese schools teach home economics, called katei-ka (家庭科), from elementary through high school. Not only do the students learn how to cook, but they also learn about the nutritional elements in food, public health, the various components that make an ichiju sansai meal, dining etiquette, and the different seasonal and local produce and foods.

Kyushoku School Meals

Many preschools, elementary and middle schools across Japan serve school meals called kyushoku (給食), which dates back to 1889. It started as a way to combat malnutrition among children, which was a severe problem at the time. An elementary school in Yamagata prefecture served the first kyushoku of onigiri, grilled fish, and tsukemono. Soon after, many schools also started serving kyushoku to their students.

It wasn’t until after World War II that kyushoku took off with the School Lunch Act of 1954. The Japanese government adopted kyushoku as a national program to not only serve nutritious meals but as an opportunity to teach shokuiku to the students.

These meals resemble the everyday meal at home, loosely based on the ichiju sansai meal. It tends to be washoku based, but non-Japanese foods such as pasta bread and cuisines such as Chinese, Korean, and Italian dishes are typical.

Most meals are made in-house at the school cafeteria, although some schools outsource the cooking to larger kyushoku centers. These meals are planned out and executed by certified nutritionists/dietitians. Kyushoku offers a variety of fresh and local produce to provide a nutritious and delicious meal for hungry students.

Nutrition Education

You may be surprised to learn that kyushoku is carried from the school cafeteria to the classroom and served by students themselves! Not only does this activity involve the students, but it also gives them a sense of responsibility and communal duty. In addition, they learn proper hygienic practices, basic food safety, and cleanup.

It’s a unique opportunity where students learn both soft and hard skills. Through kyushoku and kateika, students become consumers and participants in the complex food system, equipped with an understanding of dietary guidelines.

Highlighting the importance of nutrition and food education among the younger generation is nothing revolutionary. Many Eastern philosophies have long recognized that food’s significance goes beyond sustenance. Eating is a communal activity and an opportunity to learn about the seasonal offerings and food’s impact on the body.

My Personal Experience with Shoku-iku

Growing up in Japan, I was somewhat familiar with the concepts of Shokuiku. Throughout childhood, I preferred Japanese foods, like nimono and grilled fish. When I lived in the States for high school and college, I tried to cook the familiar comfort foods I grew up with. But the cooking was more to connect to my heritage living in an environment as a minority. It also was a social activity with friends and not connected to being in good health.

As a working adult in Japan, my life was active and busy. I didn’t have the time to think out the nutritional balance of my daily meals or research where the produce came from. Food was just fuel and a source of entertainment. While I was loosely aware of healthy foods, I didn’t think much about their impact on my body.

Teaching My Daughter About Food

After I had my daughter in 2019, I started cooking baby food, followed by meals the family could enjoy. It was then that I could reflect on what values I wish to impart to her. While I cannot always choose organic or local produce, avoid processed foods, and cook everything from scratch, I try to build a healthy foundation around food so that she can make her own decisions in the future.

For example, we expose her to Japanese food and cultural events around food. We familiarized her with the ichiju sansai setup, went grocery shopping together, and pointed out the produce she would later consume. We also read books about seasonal vegetables and fruits and get plenty of exercise. Although incremental, I try to incorporate shokuiku principles that are easy to integrate into our lives without becoming a bothersome chore.

I hope these steps have built her appreciation for Japanese cuisine and set up healthy dietary habits.

Healthy Recipes to Cook at Home

Stumped for ideas? Cooking nutritious and healthy meals doesn’t have to be plain and boring, and it can be flavorful and fun! Here are some recipe roundups to get you started.

- 12 Easy & Healthy Japanese Recipes

- 15 Best & Healthy Side Dishes to Serve with Salmon

- 15 Favorite Japanese Vegetarian Recipes

- Best Japanese Tofu Recipes You’ll Love

- 15 Delicious Miso Recipes

- Healthy Dinner Recipes You Need for The New Year

- 15 Easy Japanese Salads

- Your Guide to Japanese Vegetarian & Vegan Cooking (Tips & Recipes)

How do you incorporate healthy eating habits for yourself or your family, and what foods are you eating more/less of? Do you cook Japanese food or plan out an ichiju sansai meal? Please share in the comment box below!

Sources:

- 学校における食育の推進・学校給食の充実 – 文部科学省

- 野菜、食べていますか – 厚生労働省

- Curricular evaluation of “SHOKUIKU program” as a postgraduate minor course of food and nutrition education using a text-mining procedure – BMC Nutrition

- Japan’s School Lunch Program Serves Nutritious Meals with Food Education – NYC Food Policy Center

- On Japan’s school lunch menu: A healthy meal, made from scratch – The Washington Post

- Overview of Shokuiku Promotion – The Japanese Society of Nutrition and Dietetics

- What is “Shokuiku (Food Education)?” – Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

- Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective – European Journal of Clinical Nutrition

Thank you. This post was very interesting. After spending a week eating dinner and breakfast served at minshukus in Central Japan, pickles/tsukemono are one thing I have tried to incorporate more in my meals. It helps that I brought several varieties home from Kyoto and will make sure to buy more once I run out. The other thing I would like to incorporate on a regular basis is miso soup and seaweed.

Hi Sunflowii, thank you for reading! I hope you can incorporate tsukemono, miso soup, and seaweed into your diet! Nami has plenty of recipes in that regard, so please enjoy!

I love reading your posts and how to cook Japanese food I lived in Japan 20 years and we ate very well over there thank you

Hi, thank you so much for reading and your comment! Hope you’re still cooking Japanese food!

Love learning more about the differences in the school system from the U.S and how it ties into their overall education as citizens – very interesting about the nutritionists that help the schools plan meals. Great post!

Thank you for reading and for your kind words!

Thank you for this awesome post! So informative and helpful. I was confused by one part though, the part that said studies found that feeding rats until they’re full prolonged their lifespan but the advice is to eat until 80% full correct?

Hi ソニア!Thanks for reading and noticing the error! I’ve fixed that sentence.

Wonderful article. Seasonal foods are another thing that -nature- provides in the times we -need- such dietary intake. “Eating well” should mean that we aren’t -bloated-.. We are ready through the day for tasks physical and mental.. Only correct eating gets us there..

Hi Matthew! Thank you for reading and for your comment!

Thank you so much for this informative article. I only wish I had experienced food education as a child.

Hi Lisa! Thank you for reading. It’s never too late to start food education 🙂

An excellent article that, by comparison, highlights what is missing in North American education. I’m old enough to remember Home Economics classes where we learned to cook, shop and budget for nutritious food. Unfortunately I think the food lobby infiltrated the whole sector in the U.S. and Canada and have been allowed to advertise what is essentially lies. The availability of processed food since the 1930s parallels the rise in diabetes, heart and kidney disease in North America. A few years ago I hosted a high school student from Okinawa who was writing a paper on how to prevent U.S. style obesity in Japan. I recommended to him that Japan forbid advertising for fast food, that U.S. style fast food be heavily taxed and that Japanese children be taught the dangers of the Western diet. Glad to read that that food education starts early in Japan.

Hi Mary J, thanks for reading and for your comments! Unfortunately, fast food advertisements are prevalent here in Japan, and you can easily get a hold of junk foods. Childhood obesity is slowly becoming a problem here, but there are also preventative steps besides food education programs at schools, such as checkups subsidized by the municipal government, opportunity to get exercise via school sports programs, among others.