Ring in the new year with my Ultimate Guide to Osechi Ryori (Japanese New Year food)! Each traditional dish carries a special wish, and families enjoy this colorful feast—packed into three-tiered boxes—to welcome health, happiness, and prosperity in the year ahead. In this guide, you’ll learn the meanings behind the dishes, how modern families customize osechi, and my best tips for preparing this most important meal of the year.

Quick Overview

When I was growing up in Japan, I could hardly wait to open the beautiful osechi boxes on New Year’s Day (Oshogatsu), prepared with such care by three generations of women in my family. Each dish has a special meaning, and we enjoyed the flavors and colors while wishing for a bright year ahead.

Now, I share these traditional Japanese New Year foods with my own family. I’m excited to help you create your own osechi spread at home, no matter where you live. In this post, you’ll learn:

- the meaning and wishes behind the most popular osechi dishes;

- why we pack osechi in 3-tiered jubako boxes;

- ways to customize osechi for busy schedules and local ingredients; and

- my best tips for a stress-free osechi experience!

What is Osechi Ryori?

Osechi (お節, おせち) or osechi ryori (お節料理) is the Japanese New Year feast and the most important meal of the year.

The tradition started more than 1,000 years ago in the Heian period as a celebratory meal offered to the gods at seasonal court ceremonies. Over time, the practice spread to everyday households, and by the late Edo period, it became the New Year feast we know today.

Each traditional osechi dish carries symbolic meaning tied to its name, color, ingredient, or shape. The foods are packed in multi-tiered lacquered boxes called jubako that also symbolize good fortune.

All the dishes are prepared in advance and eaten during the first three days of the New Year, known as san-ga-nichi. Families enjoy it to welcome the new year and rest from cooking.

- See all the Just One Cookbook traditional osechi ryori recipes.

Osechi Dishes & Their Meanings

Every dish is an edible good-luck charm. From kuromame for health to kazunoko for fertility, each food carries a symbolic meaning and reflects the hopes and wishes for the coming year.

Here are the most popular osechi dishes and their meanings:

- Japanese Sweet Rolled Omelette (datemaki) – knowledge, learning, success in studies

- Sweet Black Soybeans (kuromame) – good health

- Herring Roe (kazunoko) – fertility and a growing, prosperous family

- Candied Chestnuts and Sweet Potatoes (kuri kinton) – wealth and financial fortune

- Daikon and Carrot Salad (namasu) – celebration

- Candied Anchovies (tazukuri) – a bountiful harvest

- Salmon Kombu Rolls (kobu maki) – youth, long life, and happiness (sounds like the Japanese word for joy, yorokobu)

- Decorative Fish Cake (kamaboko) – purity, warding off evil, and the first sunrise of the new year

- Pickled Lotus Root (su renkon) – good vision and looking ahead

- Pickled Chrysanthemum Turnips (kikka kabu) – longevity; celebration

- Pounded Burdock Root (tataki gobo) – family and home stability

- Simmered Taro (satoimo nishime) – family prosperity

- Simmered Chicken and Vegetables (chikuzenni/nishime) – good fortune and long-lasting happiness

- Instant Pot Nishime – good fortune and long-lasting happiness

- Simmered Shrimp – long life

- Whole Baked Sea Bream (tai) – good luck

- Yellowtail Teriyaki (buri no teriyaki) – success as you grow through life

- Butter Soy Sauce Scallops (hotate yaki) – success and a bright, prosperous future

How Do Modern Families Enjoy Osechi?

Many families still make osechi from scratch, but it’s also common to buy ready-made sets from supermarkets, department stores, and hotels. This modern approach makes it easy to keep the tradition alive, even with busy schedules. More and more households also personalize their osechi to match their tastes and lifestyle.

Here are some simple and fun ways to enjoy osechi today:

- Serve the dishes in mini jubako boxes, single-portion plates, or on one large platter.

- Mix store-bought dishes with your homemade favorites.

- Add Western-inspired and fusion dishes like roast chicken, roast beef, or smoked salmon.

- Swap local ingredients that are available where you live (yellowtail → salmon, burdock → carrots).

- Try vegetarian variations using tofu, mushrooms, kombu, carrots, and sweet potatoes.

Why Do We Pack Osechi in Jubako Boxes?

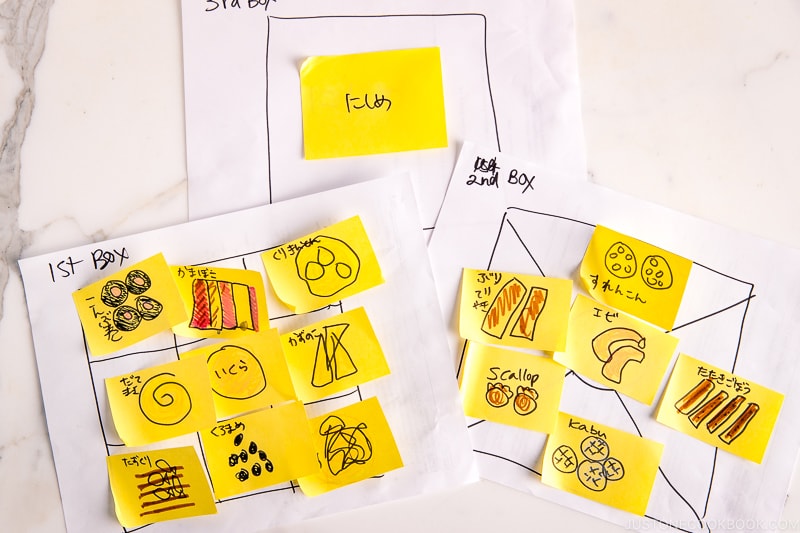

We typically arrange osechi’s colorful dishes in two- or three-tiered lacquer boxes called jubako (重箱). Each stacked layer symbolizes “piling up blessings” and the addition of more happiness and good fortune in the year ahead.

Usually, we pack delicate items and small appetizers in the top box. The middle tier contains grilled and simmered dishes. Finally, sturdy foods and other simmered dishes go in the bottom box.

For the best visual presentation, we place dishes of contrasting color, shape, and texture next to each other.

While we often follow a few traditional guidelines for packing jubako, don’t worry—they aren’t strict rules. It’s more important to focus on the meaning and good wishes this festive meal represents.

For a detailed, step-by-step tutorial, see my post How to Pack Osechi Ryori in 3-Tier Boxes.

How to Store Osechi

To store: Most osechi dishes will keep for 2–3 days in the refrigerator, and some make-ahead ones can be frozen. My recipes use moderate seasonings to keep the flavors authentic, so please avoid leaving the dishes at room temperature for too long.

Traditionally, osechi was prepared with heavy amounts of sugar, salt, and vinegar so it could last for days without refrigeration. With modern fridges, we can enjoy lighter, more balanced flavors—just be sure to store everything properly.

To reheat: Most osechi dishes are served cold or at room temperature. If you’d like to warm certain dishes, such as simmered vegetables, reheat gently over low heat or microwave in short bursts. This helps preserve the texture and flavor.

FAQs

Osechi is the Japanese New Year feast, while osechi ryori is the cuisine itself. Every dish carries symbolic meaning tied to its name, color, ingredient, or shape. For example, Japanese sweet rolled omelette represents knowledge and learning while sweet black soybeans symbolize good health.

Some families make osechi while others purchase ready-made sets from grocery stores and restaurants. Modern families will mix store-bought dishes with homemade items to enjoy the tradition even with busy schedules. For a step-by-step plan, see my Osechi Cooking Timeline.

The top box contains delicate items and small appetizers. Next, the middle box includes grilled and simmered dishes. Finally, sturdy foods and other simmered dishes go in the bottom box. For visual presentation, we place dishes of contrasting color, shape, and texture next to each other. For my complete guide, see How to Pack Osechi Ryori in 3-Tier Boxes.

While stacked boxes are traditional, it’s perfectly fine to serve on platters. Ingredients like eggs for omelet or shrimp are easy to find. Others like herring roe, candied chestnuts, mirin, soy sauce, sake, and dashi are typically found at Asian and Japanese grocery stores.

Osechi is eaten during the first three days of the New Year, known as san-ga-nichi. Families enjoy it as a way to welcome the new year, rest from cooking, and celebrate with dishes prepared in advance.

In the past, people avoided eating certain dishes during the first three days of the New Year because osechi was seen as a sacred offering and break from cooking. They refrained from beef or pork dishes (to avoid “taking life”), cooking with fire (to let the kitchen hearth rest), using knives (to prevent “cutting ties”), and hot pot dishes (to avoid the rising scum called aku—the same sound as evil). Today, most families no longer follow these rules strictly.

Yes, I do! Please check out my Osechi cookbook, Essential Japanese Recipes – Volume 3: Osechi – Japanese New Year Food!

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published on June 1, 2015, and updated on December 27, 2022, and republished on December 2, 2025 with new information.