Since ancient times, Japanese sake, or nihonshu, has been drunk at festivals, celebrations, and personal milestones. Learn about the Japanese sake culture and its significance, etymology, mythological story, and presence in Japanese society.

To the Japanese, sake is more than just an alcoholic beverage. Culturally, sake is an essential bond between the deities and mortal beings. Sake was a method of communication to appease their anger in times of natural catastrophes, pray for their blessings and protection, and thank them for a plentiful harvest. By drinking the sake offered to the gods, the Japanese believed they could become closer to them.

Even though sake is widely available and inexpensive today, its legacy remains deeply rooted in Japanese culture. It is present at ceremonies, personal milestones, and rites commemorating birth to death. Historically, the Japanese linked it to the seasons, as they would sip sake and observe nature transform. Thus, sake was the mode of connection to the gods, the living world, and the people.

Now that we’ve covered what is sake (part 1), how to enjoy sake (part 2), and the history of sake (part 3), let’s look into how sake plays a role in Japanese culture.

Table of contents

Sake and the Japanese Culture

Sake is inseparable from the Japanese religion. The two prominent Japanese religions (Buddhism and Shintoism) are also inseparable from Japanese culture. As mentioned in part 3, the imperial court, Buddhist, and Shinto leaders set up breweries on their premises. Thus, you will see sake at many religious festivals, rituals, and celebrations.

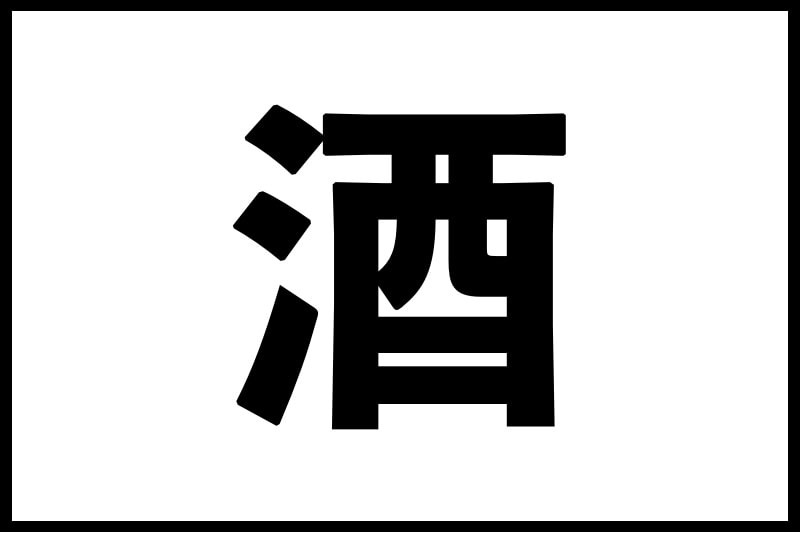

The Chinese Character for “Sake”

The Chinese character for sake 酒 is a combination of a sake cask pictogram (right) and running water (left). If you’re familiar with Chinese characters, you may notice that this sake cask character is used for other alcohol and fermentation-related terms. This includes shochu 焼酎 (Japanese distilled alcohol), moromi 醪 (the fermentation mash when making sake), moto 酛 (sake yeast starter), su 酢 (vinegar), and shoyu 醤油 (soy sauce).

In the Shinto religion, the sake offered to the gods is called “Miki” or “Shinshu” (神酒 “sake for the gods”). In the 8th-century Japanese mythological text Kojiki (古事記, Records of Ancient Matters), it calls sake “kushi” (same Chinese character as sake). This supposedly derives from the word kushiki (奇しき “strange”), as the ancient people did not know what caused the feeling of drunkenness.

Gods and the Japanese Sake Culture

Over 40 shrines and more than 55 gods related to sake are scattered across the country. Some shrines specialize in worshipping the ingredients, such as koji and brewing water. Thus, no singular god is identified as the god of sake, like Dionysus in Greek mythology.

The three prominent shrines related to sake are Oomiwa Shrine (大神神社) in Nara, Umemiya Shrine (梅宮神社) and Matsuo Shrine (松尾神社) in Kyoto. Oomiwa Shrine, also known as Miwa Shrine, is in the sacred Mount Miwa. The entire mountain is revered as the god of sake. As one of the oldest Shinto shrines in the country, it was the main shrine for the Yamato Court (250–710 AD) and where sake brewing took place.

Mount Miwa is significant for breweries to this today as Sugidama (杉玉), Sakabayashi (酒林), or Sakabouki (酒箒) are made by the trees there. It’s made of bundled cedar leaves trimmed to form a ball, then hung outside the entrance of breweries. Therefore, by hanging Sugidama made from the trees from Mount Miwa, you would be bringing a part of the god to your brewery.

Sugidama is a seasonal sign announcing the start of new sake pressing. Once hung, the leaves are a fresh green, but the leaves turn brown with time, an indicator of sake maturing. Sugidama also signifies thanks to the sake gods. There’s another theory that cedar leaves prevent the sake from spoiling, thus serving as a protective charm against unwanted bacteria.

Japanese Sake Culture and Mythology

Sake makes several appearances in the Kojiki. According to the mythological text, rice cultivation started when the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami gave rice crops to the Japanese people. When mold accidentally grew on the precious rice, the gods taught them to brew alcohol without letting it go to waste. Thus, the story goes that the Japanese are forever indebted to the gods for teaching them the knowledge of producing sake.

One of the most important stories of sake is of the monster Yamata-no-Orochi.

The legend occurs in Izumo (present-day Shimane prefecture), where the Shinto storm god Susano-o was visiting. He heard that the eight-headed serpent Yamata-no-Orochi was demanding the sacrifice of young girls every year. He got the monster drunk on strong sake called Yashiori no sake (八塩折の酒), then slew it once it fell into a stupor.

Another connection between sake and mythology is when the gods leave their respective areas to descend upon Izumo Taisha Shrine. During Kami-ari-zuki (神在月, “the month of the gods,” 10th month of the lunar calendar), the gods supposedly hold meetings about agricultural harvests, marriage unions, and the prosperity and well-being of the Japanese people. During this time, the gods feast on local sake, discuss their affairs, and depart to their respective locations after seven days.

Unlike other rowdy festivals, Kami-ari-zuki is a solemn affair in Izumo. The Shinto priests and parishioners of Izumo Taisha welcome the gods through ceremonies and rituals. Regarding this, the locals refrain from making loud noises and remain quiet. Worshippers around the country also pour into Izumo to pay their respects and pray for good fortune.

Sake at Festivals, Rituals, Personal Milestones

As mentioned in part 3, the rituals in Buddhism and Shintoism include sake. In the Shinto religion, sake was a tool to purify the shrine, spaces, and oneself. The Japanese would drink it on special occasions called hare no hi (ハレの日).

Here are just some of these cultural events where sake is present.

Japanese Sake Culture and Formal Celebrations

Kagami-biraki (鏡開き) is a ceremonial opening of a sake cask. You will see it at formal celebrations such as opening ceremonies, company parties, election victories, and wedding ceremonies.

The circular wooden lid of the barrel resembles a mirror, or “kagami” in Japanese, which symbolizes peace. By hitting the cover with a wooden mallet, opening the mirror brings blessings of health, prosperity, and happiness. Later, the group shares the sake among the assembled with a toast of “kampai (乾杯)!” (cheers in Japanese).

House Building Ceremony

When construction begins on a new house, a Shinto priest carries out a ceremony to pray for the safety of the building. Jotoshiki (上棟式 “pillar-raising ceremony”) is held once the basic structures, such as the main pillars and beams, are in place.

Everyone involved in the building construction attends the ceremony. The priest offers sake to the gods by pouring it on the ground where the building will stand to soothe the land god.

Weddings

While most Japanese couples choose Christian (even if they’re not christened) or secular weddings, some hold weddings at Shinto shrines. If you’re lucky, you may witness a traditional Japanese wedding while visiting Meiji Jingu or Kasuga Taisha!

As mentioned, sake plays a prominent role in Shintoism and, of course, at Shinto weddings. Foods such as salt, water, rice, sake, and fresh produce are displayed at the wedding altar as offerings.

The bride and groom drink sake in a ritualized ceremony called san-san-ku-do (三三九度 “three times three exchange”), where the couple sip three times from three sakazuki (盃, flat sake cups) in different sizes, starting from the smallest. Once they exchange vows, the couple passes the sakazuki to their parents and relatives, who sip sake similarly.

There are different interpretations of the symbolism of this ceremony. Some believe it represents heaven, earth, and humankind; others say it represents the love, wisdom, and happiness that grows over time through marriage. Another source says it means the three human flaws: hatred, passion, and ignorance.

Funerals

Sake is also present at funerals.

Interestingly, Japanese people do not see a problem incorporating various religions into their lives. When it comes to funerals, most choose a Buddhist ceremony. There are slight differences among the sects, but there tends to be a wake and a funeral. After the wake, the deceased’s family would invite the guests for food and drinks. The family members would walk around the tables to offer sake or beer to the guests. The guests would then eat and drink before departing.

Afterward, the family member would offer the deceased’s favorite foods and sake at the family grave and altar.

Sake Throughout the Year

As mentioned, it is impossible to separate Japanese culture, religions, and culture.

Sake was a tool to highlight seasonal beauty. It was sipped while watching the snowfall, a custom described in “The Tale of Genji.” In spring, it was while enjoying the cherry blossoms. It was drunk in the hot and humid months to ward off the heat. In the fall, it was while gazing at the full moon. Even today, many events throughout the year involve sake, including region-specific ones.

Let’s explore how sake is appreciated seasonally.

Japanese New Years お正月

Traditionally, January 1st was the most important event of the year. The new year symbolizes a renewal of life. It was also when people added another year to their age instead of celebrating their birthday. Thus, the Japanese New Year celebration has always been a festive occasion; of course, the Japanese would drink sake.

First, the entire family would slip toso (屠蘇), a sake or mirin infusion originally from China. There are some variations, but it usually includes herbs such as cinnamon, rhubarb, and sansho (Japanese pepper). The youngest would drink this herbal sake before handing it to their elders, so the joy of the youngsters passes down to their elders. The Japanese believe drinking toso wards off ailments for the year and invites peace within the household.

Sake is also drunk with osechi ryori (おせち料理), the New Year’s feast. There is no particular variety or type. However, many pick sake with auspicious names such as 開運 (good luck), 初日の出 (first sunrise of the year) or with auspicious symbols on the label, such as that year’s zodiac.

The Japanese also visit temples or shrines to pray, called hatsu-moude (初詣, “first visit”). To warm up their bodies, they drink amazake (甘酒), a sweet, low-alcohol sake with mashed rice grains. Shrines may also offer the sacred sake omiki (御神酒).

You will also see omiki offered at other celebratory events such as weddings and the children’s rites of passage 7-5-3 ceremony (七五三).

Momono sekku 桃の節句

Momono sekku, Girls’ Day or Hinamatsuri (雛祭り), occurs on March 3rd to wish and pray for girls’ health and future happiness. While children cannot drink alcohol (the legal age in Japan is 20), adults drink a special sake.

Shirosake (白酒, “white sake” with the same Chinese characters but utterly different from the Chinese distilled alcohol baiju) is sweet, thick, and cloudy. Made of steamed glutinous rice, rice koji, and shochu, it’s aged for a month and then ground up. It has a 10% alcohol content.

The origins of hinamatsuri are from joshi no sekku (上巳の節句), one of the five annual ceremonies celebrated by both genders. People would drink toukashu (桃花酒), a sake with peach blossoms floating on top. Peach blossoms were said to dispel evil spirits and bring longevity.

Around the Edo period (1603-1867), the liquor switched to shirosake, a thick and cloudy sake. Due to its pure white color, it was said that drinking it would purify the body. It was around then that the custom of drinking it became widespread.

Another type of sake drunk at this time is amazake. If made from sake lees, it contains low amounts of alcohol. The non-alcoholic version contains rice and rice koji, suitable for children and those with low alcohol tolerance. It’s also thick and looks like shirosake.

Obon お盆

Obon is a Buddhist custom that honors the family ancestors. Depending on the region, it’s a three-day event between July and September (depending on the solar and lunar calendar).

The family members would offer incense sticks, candles, water, flowers, and food to the altar. They would also offer sake to the altar or family tomb called okurizake (送り酒 “send-off sake”).

Tsukimi sake (月見酒)

Like many Asian countries, the Japanese celebrate the mid-autumn festival called Otsukimi (お月見). All social classes widely celebrated the custom during the Edo period.

The people would display pampas grass, yams, edamame, and dango to thank the gods for another successful harvest. They would then gaze at the full moon and drink sake. Nowadays, drinking sake by moonlight is more of an aesthetic pleasure than a symbolic ritual.

Japanese Sake Culture and the Seasons

Did you know that there is seasonal sake? As the Japanese love and respect the changing seasons, breweries produce sake to suit the four seasons. The taste and aroma of the sake differ due to the difference in maturation. Breweries also develop creative names and labels to suit the season and festivities. Sake drinkers eagerly anticipate the annual rollout of these seasonal releases.

Breweries do not follow the typical Gregorian calendar. Instead, they start the year on July 1st and end on June 30th the following year. Breweries kick off the sake brewing process in the summer by checking and cleaning their machinery and equipment. Sake production then goes into full swing around September with the rice harvest. Once breweries finish the sake production cycle in March, they store the sake in tanks, wooden vats, or bottles to mature.

In addition to the styles mentioned in part 1, let’s look at the different seasonal sake.

Winter Sake

Shinshu (新酒 “new sake”) is sake produced that year. You’ll see shinshu from the winter to spring months and as early as November. It has a shorter maturation than the other seasonal sake, like the French wine Beaujolais Nouveau.

Shinshu has a characteristic freshness and is lightly bubbly. Many do not undergo hi’ire (火入れ pasteurization) and are labeled namazake (生酒 “raw sake”). As namazake skips the pasteurization process, the enzymes and microorganisms are still active, making it extremely sensitive to its environment.

Another type of namazake is shiboritate (しぼりたて “just pressed”). While it lacks the umami richness of regular matured sake, it’s light, refreshing, and flowery.

Nigorizake, or nigori (にごり酒), is also a favored winter/spring sake. It’s made by straining the sake through a coarse cloth after fermentation to leave the yeast and rice particles. The cloudiness resembles fluffy snow.

Autumn Sake

Autumn sake has matured through the summer and has a mellow and well-rounded flavor. There are two types of autumn sake: Hiya oroshi (ひやおろし) and Aki agari (秋あがり).

Hiya oroshi is pasteurized once (typically, sake is pasteurized twice, once before bottling and before shipping). It’s both mellow in flavor and also fresh. Aki agari refers to sake that has matured until the fall, regardless of pasteurization.

Summer Sake

Natsuzake (夏酒 “summer sake”) is a newcomer to the sake scene. Sake breweries coined the term to combat declining sales during the stagnant summer months. Therefore, there’s no distinctive style of summer sake.

Spring Sake

Spring sake is available from late February until April. It’s aptly called Hanami zake (花見酒 “sake for hanami“) or Haruzake (春酒 “spring sake”). Spring is also the end and start of the new year for the Japanese, graduation, and farewells, and when the school and business year starts. It’s a time of departure, new beginnings, and joyous celebrations.

As you may know, the Japanese have historically treasured the spring season. The history of hanami (cherry blossom viewing) dates back 1,000 years. The nobility and commoners would drink, eat, sing, and celebrate under the cherry trees. Many partake in hanami today, although non-sake alcohol can also be preferred.

Some sake brewers may tint it a light pink by coloring the yeast or using yeast derived from cherry blossoms. It may be lightly sweet and flowery, hinting at the spring season.

Japanese culture centers on the respect and worship of nature and ancestors. The Japanese make offerings to the gods and their ancestral spirits and ask for their protection and blessings in return. As rice and its by-products were the most valuable offerings, sake is one of the finest offerings to the gods. Legends say the gods loved drinking sake as much as we did!

Sake also serves as a medium to connect the celestial beings and mortals and brings people together. From ceremonies, rituals, personal milestones, and more, sake continues to be ingrained in the Japanese culture. I hope you enjoyed reading about the Japanese sake culture, and I would love to hear from you in the comments below.

Learn about the Japanese Sake

- Sake Guide for Beginners

- How to Enjoy Sake (Food Pairings Included)

- A Detailed History of Japanese Sake

- The Japanese Sake Culture – An In-Depth Guide

Sources: