What is sake? How is it made, and who makes it? Learn about the different styles and varieties of this ancient rice-based brew.

Sake, “rice wine,” or “nihonshu,” is ubiquitous in Japanese cuisine and culture. The history and culture of sake are closely intertwined with the Japanese civilization. The Japanese drink sake at festivals and ceremonial events throughout the year and at mealtimes every day.

So, what is sake? Let’s examine the centuries-old brew, starting from the ingredients, the process of sake making, the different styles and varieties, and the people involved.

This sake guide is the first of a four-part series delving into the world of sake.

Table of contents

What is sake?

Sake (pronounced sah-keh) is an alcoholic beverage brewed from rice, koji (Aspergillus oryzae), yeast, and water. In Japanese, “sake” refers to all alcoholic drinks. The Japanese word is Nihonshu (日本酒), “Japanese alcohol,” or more technically, Seishu (清酒), “clean alcohol.”

Sake has an alcoholic content of 15-20%, and it can be clear, straw-yellow, or cloudy. The flavor can range from hearty umami-rich to light and acidic. Depending on the type, the taste can be fruity, like melon or apples. It can be robust and heavy or dry and light like white wine.

New styles of sake have emerged in recent years, adding a new spark to the industry. From bubbly sake similar to champagne to sake made to pair with non-Japanese cuisine, new styles, and technological advancements, the world of sake is evolving in the 21st century.

Sake Gaining Worldwide Popularity

The Japanese National Tax Agency defines “nihonshu” as sake made with domestically sourced ingredients. All stages of production, from brewing to bottling, must take place in Japan. This rigid classification system is similar to Geographical Indication (GI), like the wines from France and Italy.

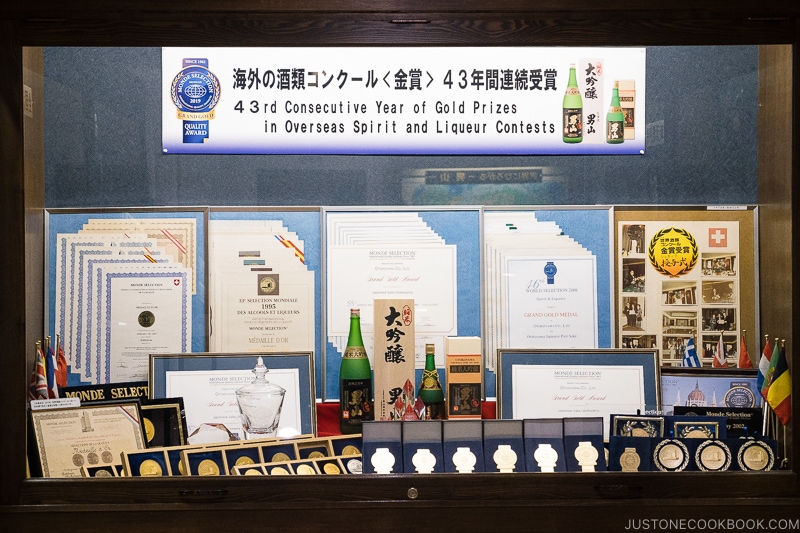

In recent years, sake has been gaining traction outside of Japan. The International Wine Challenge (IWC), the world’s largest wine competition, added a sake category in 2007. Since then, many sake brands have received high praise and recognition outside Japan. Breweries outside Japan, including the U.S., Canada, Brazil, and China, have also popped up. While this sake may not follow the strict guidelines of Japanese liquor laws, sake has a huge fan base worldwide.

What’s in sake?

As mentioned above, there are four elements involved in sake.

- Rice

- Koji

- Yeast

- Water

Rice for Making Sake

Like wine grapes differ from eating grapes, rice for sake differs from short-grain rice. Sake rice is called saka-mai (酒米), shinpaku-mai (心白米) or more formally shuzo koteki-mai (酒造好適米). These rice strains are bred to make the grains larger, more firm, higher in starch, and contain less protein and lipid. The rice plant is taller, has longer ears, and produces more rice grains than the table rice plant.

There are at least 100 types of sake rice. Over decades, many were cross-bred to create strains that adapt to the local terroir for the ultimate flavor profile. The most well-known varieties are Yamadanishiki (山田錦), Gohyakumangoku (五百万石), Miyamanishiki (美山錦) and Omachi (雄町).

Varieties of Rice

Yamadanishiki, AKA “the king of sake rice,” is the most popular, most commonly grown, and expensive. Primarily grown in Hyogo prefecture and across southern Japan, it’s known for producing delicate, aromatic, feminine styles of sake. Many premium sake, such as ginjo, use Yamandanishiki.

Using sake rice for sake production is relatively new. Traditionally, brewers made sake with table rice. Over time, they bred rice specifically for sake brewing with the desired attributes. In 1951, the Japanese government recognized sake rice and gave the designation Shuzo koteki-mai (酒造好適米), “rice appropriate for sake production.”

Sake rice is just 2% of total rice production, of which Yamadanishiki and Gohyakumangoku make up 60%. However, some breweries have switched from popular varieties to lesser-known and locally produced strains to diversify their sake.

Futsu-shu (普通酒), “normal alcohol,” is non-premium sake. It’s made with table rice, contains additional alcohol, additives, and flavorings, and is much more affordable. Futsu-shu includes sake in paper cartons, single-serving sake in glass vessels, and cooking sake. This does not dismiss futsu-shu as poor sake; they can be fine for casual drinking, and some breweries use broken sake rice to avoid waste. But in terms of designation, these sake would qualify as futsu-shu.

Premium sake made with 100% sake rice called tokutei meisho-shu (特定名称酒), “special designation sake” accounts for 25% of domestic sake production (more below).

Koji

Koji (麹菌) is instrumental in making Japanese staple condiments such as soy sauce, mirin, miso, rice vinegar, and sake! The fuzzy fungus naturally grows on rice, although it can also grow on other grains like barley and soybeans. It is a cultivated microorganism with enzymes that convert the rice starch into glucose and protein into amino acids.

The koji used for sake is koji rice (米麹), AKA malt rice or Aspergillus oryzae. It’s made by inoculating steamed rice with the mold and then wrapping it in a blanket to incubate. The spores germinate for 50 hours, forming a crumbly dry material. Koji rice makes up around 20% of the total weight of polished rice used for making sake.

Historically speaking, koji was most likely imported from China. However, the Japanese method and ingredients differ from the Chinese koji, called Qū (曲/麹). Cereal flour (wheat, barley, rice, or peas) is the principal ingredient in Chinese koji. It is kneaded into bricks and incubated in a warm and humid environment to ferment. The Chinese use this koji to brew alcoholic beverages such as huangjiu (cereal wines), baijiu (distilled spirits), and condiments like soy sauce, fermented tofu, and doubanjiang.

Yeast

Yeast/shubo (酵母) doesn’t get much attention compared to the other ingredients but is vital in sake production. Sake needs yeast to produce alcohol as the yeast feeds on the glucose broken down by the koji. It then generates ethanol and carbon dioxide, which is the fermentation process.

Yeast exists naturally, but specific varieties exist for food production. Sake is brewed with the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Brewing Society of Japan (日本醸造協会) produces different strains called kyokai sake yeast (きょうかい酵母), which breweries use to make sake. The pure yeast strains were created by isolating naturally occurring yeast in sake tanks.

The yeast influences many elements of sake, such as the aroma and taste. The Brewing Society is constantly developing new yeast strains. There are currently 15 publicly available yeast strains, although some are defunct due to having undesirable attributes. The strains are assigned numbers, each with unique qualities. K-4 is the most commonly used, and K-9 is often used for ginjo.

Water

Sake is 80% water, so it’s no surprise water is a definitive player in sake production. Called shikomi mizu (仕込み水) “training water,” breweries strategically locate themselves in areas with good water sources. They may secure their supply of well water or underground water. Sake rice and koji can be brought over, but transporting enough water is complicated. Thus, sourcing ample water is vital.

Water is used to clean the manufacturing equipment, wash, soak, steam the rice grains, and dilute the final product. However, not all water sources are suitable; one of the determining factors of shikomi mizu is low traces of iron and manganese. High amounts of these minerals can hinder the fermentation process and spoil the aroma and taste of the sake.

Water in Japan tends to be soft water (low mineral content), which yields slow fermentation for a smooth, sweet, low acidic sake. The water from Fushimi in Kyoto prefecture, called Gokousui (御香水), is famous for these qualities. But there are water sources with hard water (high mineral content), notably Miyamizu (宮水) in Nishimiya, Hyogo prefecture. This water yields sharp, dry, and firm sake with high acidity. Not surprisingly, Hyogo prefecture boasts the highest number of brewers.

This is not to say that only natural water can do. Urban breweries in Tokyo source purified municipal water and brew quality sake.

Rice Milling

So, what’s the secret to that clear and refined taste of sake? It’s due to the polishing or milling of the sake rice.

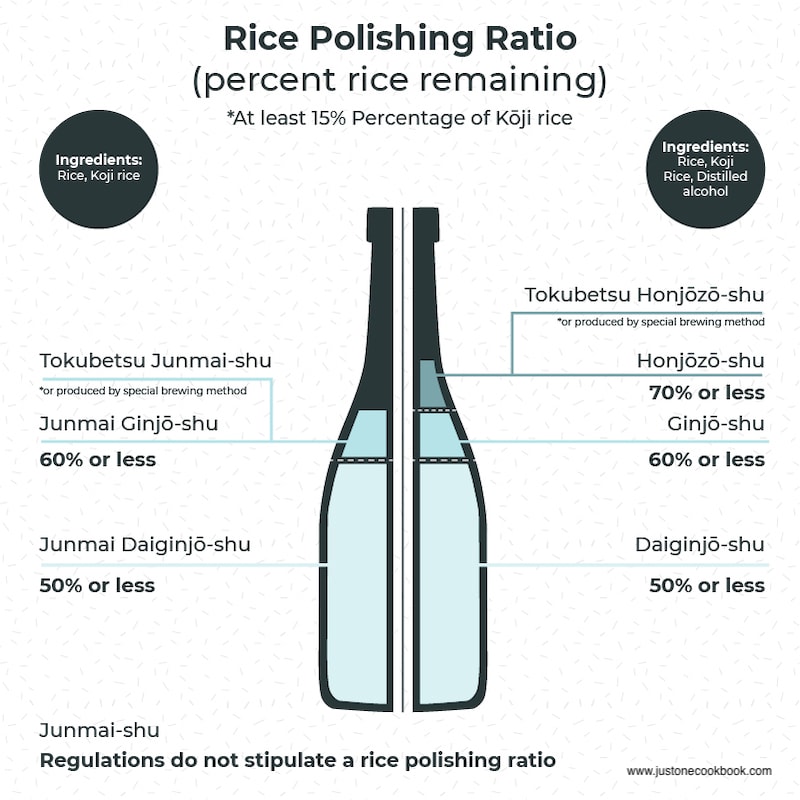

Seimaibuai (精米歩合) refers to the percentage of rice remaining after polishing. You can read the sake’s grade from this percentage. More milling equals more expensive and premium; it is laborious to mill each grain while keeping it intact. Milling rice is a delicate and time-consuming process that can take upwards of a few days. For context, milling the rice to a 23% polish rate (77% is milled) may take 168 hours or one week.

So why go through the expensive and intensive process? The outer layers of rice grains house nutritional components like protein, fats, and lipids. These attributes are great for eating but bad for brewing, as they can create unwanted flavors in the sake. Brewers mill the outer layers to work with the starchy rice grain core called shinpaku (心白).

The polish rate can alter the sake’s flavor, aroma, and characteristics. More polishing produces light and delicate flavors, whereas less polishing makes full-bodied sake. But more polishing does not necessarily entail higher quality sake. Some breweries believe that excessive polishing results in losing the rice’s characteristics and unnecessary waste. So they use minimally mill the rice to produce sake that still tastes clear and refined.

The discards from sake making are reused for other purposes. The rice bran from polishing can be repurposed into animal feed, fertilizer, rice flour, and more. The by-product from pressing out the sake is sake kasu/sake lees (酒粕), which has about 8% alcohol content. It’s highly nutritious and is used to make nukazuke and amazake. Some cosmetic companies make skincare products with sake lees as it contains amino acids, which may help with skin hydration.

Sake Classification

In terms of sake classification, deciphering it can be a little confusing. There are rigorous standards regarding sake rice, rice milling, and distilled alcohol. Many breweries release different styles under the same brand name. The milling ratio indicates the sake’s profile, and the price doesn’t necessarily correlate to quality.

The different types of sake can be overwhelming but do not worry. You’ll find your personal preference once you start trying sake.

Below are the eight classifications for ingredients, rice polishing ratio, and production method.

Junmai Sake

Junmai-shu (純米酒) – Composed of the Chinese characters “pure rice,” this refers to sake made solely from rice, koji, and water. Its designation is exclusively from its ingredient list and does not require a polish rate. Junmai tends to have a rich and robust body with slight acidic notes, subdued aromas, and rice-influenced flavors.

Tokubetsu Junmai-shu (特別純米酒) – A type of junmai with a polish ratio of 60% or less and produced by a special brewing method.

Junmai Ginjo-shu (純米吟醸酒) – A ginjo made of rice, koji, and water with a 60% or less polish ratio.

Junmai Daiginjo-shu (純米大吟醸酒) – The most premium and high-quality sake. Delicate, full-bodied, and rich, it’s the most premium sake.

Distilled Alcohol Added

Honjozo-shu (本醸造酒) – The weight of the added alcohol is no more than 10% of the weight of the sake rice. Generally speaking, honjozo-shu tends to be lighter and drier than junmai and pairs well with most Japanese foods. Think of honjozo as casual table sake.

Tokubetsu Honjozo-shu (特別本醸造酒) – Tokubetsu (特別) means special and refers to a special brewing method defined by the brewery. As there is no definition for what constitutes a special brewing method, this is at the discretion of the brewery.

Ginjo-shu (吟醸酒) – Sake made from rice, koji, water, and distilled alcohol with a polish rate of 60% or less. Ginjo differs from other types of sake in its brewing process. It requires labor-intensive techniques such as long fermentation, maturation, and delicate pressing of the sake from the mash. Ginjo is delicate, balanced, fragrant, and complex, and has a fruity floral flavor. Serve chilled to enjoy the refined tastes. The ginjo style is a relative newcomer to the sake scene.

Daiginjo-shu (大吟醸酒) – Daiginjo, literally “big ginjo,” refers to sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 50%. It is the most prized of sake varieties and represents the brew master’s mastery. Each brewing process undergoes meticulous care and is brewed in smaller tanks to regulate the temperature and fermentation speed.

Other Notable Types of Sake and Terminologies

Here are some terminologies you may encounter in addition to the categories above.

Dobukuro (濁酒) – Doburoku is a cloudy and chunky sake that was traditionally home-brewed. It’s lower in alcohol than sake and is made by mixing steamed rice, koji, water, and starter mash. Dobukuro has mostly disappeared from the sake scene due to the ban on home brewing.

Genshu (原酒) – Undiluted sake. It has a high alcohol content with a strong flavor.

Jizake (地酒) – Local sake made in the local region by small or artisan breweries.

Kimoto (生酛) – A traditional and orthodox method of brewing sake that dates back 300 years. It’s made by grinding the steamed rice with an oar into a mash to produce a fermentation starter called Yamaoroshi (山卸し).

Koshu or Jukusei-shu (古酒・熟成酒) – While there are no legal guidelines, koshu refers to sake aged for at least a year up to 10 years. Aged in barrels, steel tanks, bottles, refrigerators, or at room temperature, the taste is smooth, complex, and often compared to sherry or brandy.

Muroka (無濾過) – Sake that does not undergo a second filtration. This type of sake tends to have a yellowish hue and fuller-bodied flavor.

Namazake (生酒) – Unpasteurized sake.

Nigori-shu (濁り酒) – Nigori has a cloudy appearance consisting of rice solids filtered through a coarse mesh. The texture is creamy, and the flavor can range from dry to sweet.

Shinshu (新酒) – Literally, “new sake,” a sake produced that year.

Taruzake (樽酒) – Sake aged in Japanese cedar barrels with a characteristic spiciness. You will see taruzake at ceremonies, celebrations, and weddings in a kagami-biraki ritual (鏡開き).

Yamahai (山廃) – The abbreviation of yamaoroshi haishi moto (山卸廃止酛), it’s a traditional fermentation. Unlike kimoto, the yamahai method omits the grinding process, and instead, the koji enzymes break down the rice.

How is Sake Made

While sake is known as “rice wine,” the process is like brewing beer. However, unlike beer, the enzymes for the starch conversion come from malt; in sake, it is with the help of koji.

Sake production begins with milling the harvested rice in the fall and continues until the last filtration process in the spring. The sake brewing process is a complex multi-step process.

Sake brewing can be divided into three main steps: making the koji rice, fermentation starter (moto/shubo 酒母・酛), and fermentation mash (moromi 醪).

Sake Making Process

There are some exceptions, but the process is as follows:

- Polishing the rice

- Washing and soaking the rice

- Steam-heating the rice

- Sprinkling koji on the rice to make koji rice

- Making the fermentation starter by combining the koji rice with more steamed rice, brewing water, and yeast

- Transferring this starter to a large tank where more steamed rice, koji rice, and water is added in three batches to make the fermentation mash

- Adding distilled alcohol to the mash (if brewing non-junmai sake)

- Pressing this mash to separate the sake from the sake lees

- Removing the sediments, filtering, diluting, pasteurizing, maturing, and bottling the sake

This is a significantly simplified explanation of the sake-making process. Please read these posts by Sake Times and Japan Sake for further reading.

Sake Breweries

Sake production takes place in Sakagura (酒蔵) or Shuzomoto (醸造元). According to the National Tax Agency, over 1,400 registered breweries produce 10,000 styles of sake (2016 data). As mentioned, Hyogo prefecture boasts the most breweries nationwide, followed by Kyoto and Niigata.

Breweries exist across the country wherever rice is grown. The prefectures with the fewest breweries are Miyazaki, Kagoshima, and Okinawa. They produce the distilled alcohol shochu (焼酎) and awamori (泡盛).

Players Involved in Sake Production

Sake production is a labor-intensive process that requires many players. It’s a team effort and a seasonal project where the workers live and eat together for half a year. Sake production is an intensive 24-hour process (as the microorganisms do not adhere to an 8-hour workday schedule). Thus, workers live under the same roof with almost no days off.

Traditionally, seasonal workers worked at breweries, mostly rice farmers finished with the year’s harvest. However, a growing number of breweries employ their workers year-round.

Sake production requires the following people:

Toji (杜氏): The brewmaster, the chief executive of the entire sake production. Toji is highly respected as they have passed the national brewing accreditation and inherited the skills in making quality sake.

Kashira (頭): The #2 who assists the toji. S/he gives instructions to the other workers and is also responsible for procuring materials and budget control.

Kojiya (麹屋) or Daishi (代師): Person in charge of making the koji

Motoya (酛屋): Person in charge of producing and monitoring the yeast starter

Kamaya (釜屋): Person in charge of washing and steaming the sake rice

Sendou (船頭): Person in charge of pressing the sake

Oimawashi (追廻し): The lowest rank worker, in charge of various odd jobs

Meshiya (飯屋): Person(s) preparing staff meals. Newcomers take on this role first before rising to the ranks. Some breweries separately hire temporary workers, usually local women, to take on this role

Kurabito (蔵人) or Sakagura (酒蔵): Refers to all workers involved in the brewing process, sans the toji

Kuramoto (蔵元): Refers to the brewery owner(s), which may include the owner’s family

Future of Sake Brewing

As toji have dwindled in recent years, some breweries have dropped the hierarchy system. Instead, they train their workers to become brewing generalists by shuffling them around positions. Young people, women, and non-Japanese workers are entering the field, sparking new interest in sake.

I highly recommend the following to learn more about the world of sake.

- Documentaries: Birth of Sake, Kampai! For the Love of Sake

- Manga: Natsuko no Sake (夏子の酒), Wakako Sake (ワカコ酒), Sake no Hosomichi (酒のほそ道), Nihonshu ni Koiwo Shite (日本酒に恋をして) (some are available in English and other languages)

Curious to learn more? I suggest checking out the glossary page on SAKETIMES and Urban Sake for more sake terminologies.

I also recommend the sources listed below for a more in-depth reading.

In part 2, let’s go over how to enjoy sake at home or in restaurants. We’ll cover drinking temperatures, drinking cups, vessels such as tokkuri, ochoko, masu, drinking etiquette, food pairings, and more.

Learn about the Japanese Sake

- Sake Guide for Beginners

- How to Enjoy Sake (Food Pairings Included)

- A Detailed History of Japanese Sake

- The Japanese Sake Culture – An In-Depth Guide

Sources:

Although I’m sure that you could use any of all of the types of Sake for cooking. What types are considered acceptable for cooking and the best for cooking {If different} ?

Hi Logan! For cooking sake, I would suggest looking for something that doesn’t have salt or additives (which is helpful in preserving its shelf life but the added sodium may screw up your cooking). Here’s post on sake and mirin, which also has photos of Nami’s favorite sake brands. Hope this helps!

This was a helpful article. The methods of brewing were fascinating. This is a lot of different information all at once. I would like brand names representing the different types. It would make it easier for us less informed types. Thanks.

Hi Tom, thank you for reading! It is a lot of information, and there’s so much more out there so please stay tuned for the next 3 posts and check out the suggested readings I listed on the post.

As for your question regarding brand names, it’s difficult to suggest names as most breweries release different types of sake under the same brand name. For example, the Niigata sake Hakkaisan 八海山 releases a huge range of sake varieties under the Hakkaisan brand (tokubetsu honjozo, junmai, daiginjo, nigori, etc etc).

In addition, some may not be available outside of Japan and thus are difficult to procure for those not based in Japan. I would suggest finding a reputable liquor/sake store/Japanese supermarket that sells sake and talking to someone there who can guide you. Sorry I can’t be of much help!

I really enjoyed reading this article. I enjoy sake and am keen to learn more about it. ありがとう

Hi Allison! Thanks for reading! Please do check out the other (and more in depth) content I shared on the post as well!

Never ever thought about all those many details about sake. For me it’s been like different sake producers but nothing more. It’s been a really interesting read. Good work.

Hi P Gras, thanks for reading! Glad this article was helpful 🙂

A very informative and well written article. Thanks .

Hi S Alberts, thanks for reading and the kind words! Please stay tuned for part 2!